I Can See London From My Saddle

/

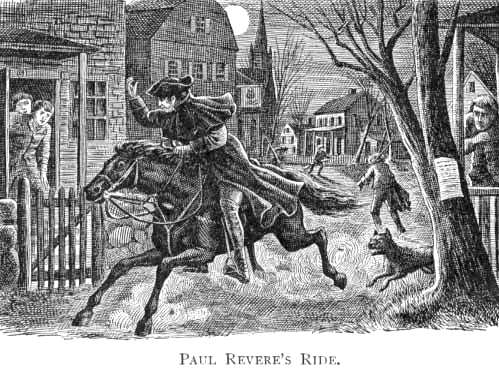

There's been some great debate this past week over Kristen Lamb’s post Sacred Cow-Tipping–Why Writers Blogging About Writing is Bad. It certainly made me think about what I blog about here on Skeleton Keys. From the beginning, this blog has had a split focus because I’ve posted about both writing and forensics/forensic anthropology. But Kristen made me think about expanding my focus a bit to include other interests that apply directly to my current crime fiction series: architecture, science in general, and the history of Boston, Salem and Essex County, Massachusetts in particular. Combine that with Sarah Palin’s recent faux pas in Boston, and this blog post was born.

Mrs. Palin recently said about Paul Revere: “He who warned the British that they weren’t going to be taking away our arms by ringing those bells and making sure as he’s riding his horse through town to send those warning shots and bells that we were going to be secure and we were going to be free and we were going to be armed.”

That’s not quite how it happened.

The Old North Church (Christ Church) in Boston

Revere, a member of the Sons of Liberty, spent the winter and spring of 1775 staying one step ahead of the British, riding from town to town to alert the townsfolk about the movements of the local British troops. Those troops mached through the countryside under orders to confiscate any and all armaments for their own use. But they found that each town they approached had already hidden away all their arms thanks to the tenacious Sons of Liberty, leaving the Redcoats humiliated and empty-handed. In an effort to circumvent the Sons of Liberty, General Gage, leader of the British troops, concocted a secret plan ― on the night of April 18, 1775, the British would move under the cover of darkness and conduct a surprise raid on Lexington and Concord at dawn when the patriots were unprepared. History suggests that either Gage’s wife or maid betrayed him to the Sons of Liberty, sharing the secret of the dawn raid. But on the night of April 18th, there was still some question about how the troops would move.

Revere intended to ride himself to warn local patriots, but he arranged for Robert Newman, caretaker of the Old North Church in Boston, to broadcast important information concerning troop movements by lighting either one or two lanterns in the church steeple. One lantern meant the troops were moving by land; two lanterns implied the British were crossing the Charles River by boat. A former bell-ringer himself, Revere knew that the signal would be clearly visible across the harbour, alerting his countrymen even if he was caught.

At 10 p.m. on the night of April 18, 1775, Newman climbed the steeple to hold aloft two lanterns for less than a minute. The light was seen across the harbour by patriot eyes, but the British in Boston also spotted it and the chase was on. Newman managed to flee the church by leaping through the sanctuary window (now known as the ‘Newman Window’) even as the British were trying to come through the front door. Today, hanging in front of that window is a replica of the lanterns that were used that night.

The Newman Window

Revere rode out that night, first crossing by boat from Boston to Charleston and then riding through Medford and on to Lexington. He didn’t ring bells or shout ‘The British are coming! The British are coming!’ ― this was a time of subtlety and espionage; secrecy was paramount because many colonists were still loyal to the British. But his ride set in motion a chain of fellow riders; it is estimated that there were over forty messengers riding that night, warning fellow patriots of the oncoming army.

Captured and questioned at gunpoint by the British, Revere did warn them of the size of the force they were about to confront in Lexington, recommending they abandon the attempt. Nevertheless, his captors continued towards Lexington. But after seeing the militia gathered there, they released Revere, confiscating his horse to ride east to warn the approaching army. As the sun rose, Revere helped John Hancock and his family escape Lexington, even as the opening shots of the American Revolution sounded as the Battle of Lexington began.

One of the best known versions of the events of that night was written by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, a native of Cambridge. I’ve included a small excerpt from it here:

He said to his friend, "If the British march

By land or sea from the town to-night,

Hang a lantern aloft in the belfry arch

Of the North Church tower as a signal light,--

One if by land, and two if by sea;

And I on the opposite shore will be,

Ready to ride and spread the alarm

Through every Middlesex village and farm,

For the country folk to be up and to arm."

2.1%

2.1%