Biosecurity Incidents In Top U.S. Labs—What, Me Worry? Smallpox Edition

/

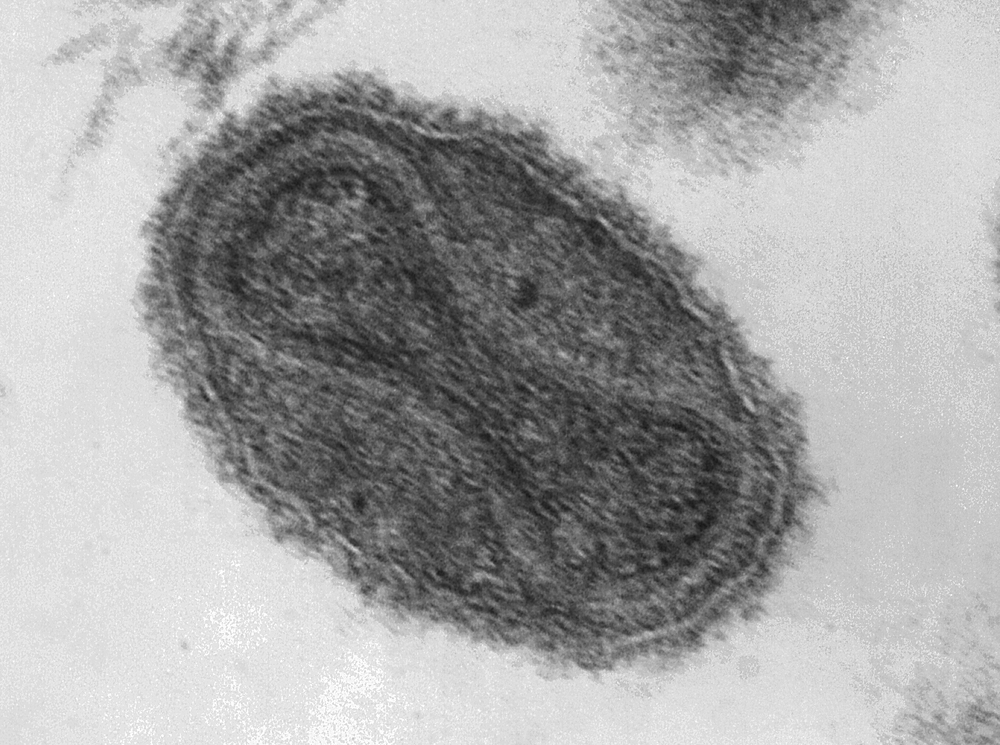

Smallpox is one of the few diseases that modern medical science has managed to eradicate. Believed to have emerged around 10,000 B.C., the disease first appeared in historical documents in the 15th century. The disease is estimated to have killed 300 to 500 million people in the 20th century alone, having a fatality rate of 20–60% in adults and 80% in children.

Smallpox is widely taught in university immunology classes as the world’s first vaccine. Edward Jenner noticed in 1798 that milkmaids who developed cowpox seemed to be immune to smallpox infection. In a stunningly unethical, off-the-cuff experiment, when a milkmaid came to him for treatment, he ran a thread through one of her pustules, coating it with pus. He then inoculated the eight year old son of his gardener by making a small cut and running the pus-coated thread through it. Shortly after, the boy became symptomatic for a mild case of cowpox. Several months later, Jenner took pox scabs from someone with small pox and similarly inoculated the boy a second time. The boy was immune to smallpox and remained healthy. This was the beginning of the vaccine revolution.

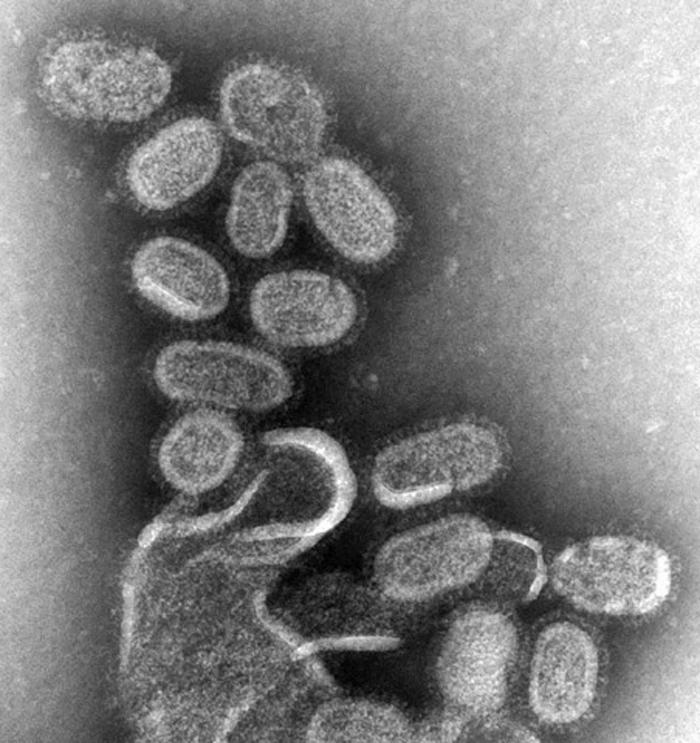

In 1967, the WHO mandated the eradication of smallpox, using newer, modern vaccines based on vaccinia virus, a virus related to both smallpox and cowpox. The last known case of smallpox occurred in 1977, and the WHO considered it eradicated in 1979.

This left the world with only laboratory strains of the virus. Following a breach of containment, resulting in the death of a lab worker in 1978, any labs with remaining virus either destroyed them or transferred them to safer labs. Currently, only the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and the Russian State Research Center for Virology and Biotechnology still retain samples. The argument has been made that all remaining virus should be destroyed, but the existing aliquots are retained in case any other stocks arise leading to a dangerous bioweapon in the wrong hands. At this point, decades after the final vaccinations, essentially everyone except military personnel (who continue to be inoculated with the vaccinia vaccine for out of country work) would be susceptible to a fresh onslaught of smallpox. But with only two stocks of the virus in the world, we’d like to believe that we’re safe.

So it was somewhat of a shock in July 2014, when the National Institutes of Health reported that six glass vials of freeze-dried smallpox stock had been found in a long forgotten box in the back of a cold storage room. I remember hearing the news and being stunned for several reasons—glass vials to store a biosafety level IV pathogen (of course, there was no sterile, disposable Nalgene polypropylene cryovials back then, but glass? So incredibly dangerous…), no security, and no inventory so no one even knew they were there. The stock was estimated to have been there since the 1950s, even though the building didn’t open until the 1960s, and from the 1970s on was used by the Food and Drug Administration. A further investigation reveals twelve boxes in total containing smallpox, dengue, influenza, Q fever, and rickettsia, all previously unknown to be stored there, and all with no security precautions (proper security precautions would involve a minimum of two locked doors between the pathogen and the public, detailed inventories, and full biosafety training of all personnel). The FDA immediately mandated a full review of all cold storage spaces to ensure no other pathogens were present.

The glass vials were immediately transferred to the CDC to undergo testing, where it was determined that two of the six vials contained viable virus. Had the tubes broken, the world could have seen a smallpox pandemic the likes of which it hadn’t seen for decades and for which we are entirely unprepared. Luckily for all of us, the vials remained intact. All the vials were destroyed following testing.

Ann and I are going to be taking some time off for summer holidays and to really concentrate on drafting LONE WOLF, book one of the new FBI K-9 Mysteries with Kensington Books. So we look forward to coming back fresh and with a lot of solid writing behind us in September. See you then!

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

12.1%

12.1%