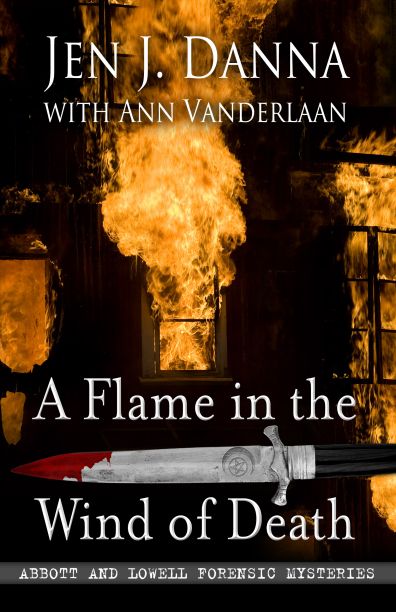

Amazon has the hardcover version of A FLAME IN THE WIND OF DEATH listed for May 9th release, but we’re happy to announce that the ebook version is now available! So for those who are looking for instant gratification, you can find the Kindle version of book 3 of the Abbott and Lowell Forensic Mysteries for a cheap and cheerful $3.19: A FLAME IN THE WIND OF DEATH. If you'd like to wait for the hardcover version, Amazon currently has it for pre-order at nearly 40% off here. For Canadian readers, Chapters/Indigo is carrying the book online and in store. And if you’re thinking ‘Book 3? What happened to book 2?’, our series novella, NO ONE SEES ME ‘TIL I FALL, is available for Kindle here. There's still time to catch up if you've only read DEAD, WITHOUT A STONE TO TELL IT so far!

For those who are wondering if they’d like to try the novel Kirkus called ‘A tricky mystery rich in intriguing suspects and forensic detail’, here’s a sneak peek at the first chapter. Enjoy!

CHAPTER ONE:

FIRE POINT

Fire Point: the temperature at which a fuel produces enough vapor so it continues to burn after ignition.

Sunday, 1:24 p.m.

Harborview Restaurant

Boston, Massachusetts

Sunlight sparkled in lightning-quick flashes on the open ocean as a lone black-backed gull soared on outstretched wings, motionless on the breeze. In the harbor, sailboats unfurled yards of canvas to the cool fall winds, while high above the water, the historic Customs House Tower stood watch over the busy port below.

Inside the restaurant, wide panels of sunlight fell across linen-draped tables set with china and silver. The air was fragrant with garlic and peppercorn as a low buzz of conversation filled the room, punctuated by bursts of laughter and the clatter of dishes.

“And then he jammed his gun in his pants to make a run for it. But while he was wedging it under his belt, it went off and he shot himself in the foot.” Leigh Abbott paused to sip her mimosa. “After that, the foot chase was pretty much a technicality, what with all the limping and whimpering.”

Matt Lowell chuckled as he set his knife and fork on the edge of his empty plate. “I shouldn’t be laughing, should I?”

“Because he’s a murder suspect?” One corner of her mouth tipped up in an almost reluctant smile. “Welcome to cop humor; it’s how we survive the job. This guy was a mistake waiting to happen from the second it occurred to him he could have the family business all to himself after his father died. He just needed to kill his brother to get it. He left a trail of clues a blindfolded rookie could follow.”

Matt’s smile slowly melted away, his face growing serious. “You deserve an easy case. After the last few weeks . . .”

His voice trailed off, but Leigh understood, even without words.

A Trooper First Class with the Massachusetts State Police, Leigh was a member of the Essex County Detective Unit, headquartered in Salem. When a single human bone was found in a coastal salt marsh the previous month, she’d approached Dr. Matthew Lowell in his capacity as a forensic anthropologist at Boston University to help identify the victim. What began with a single set of remains rapidly spiraled into ten murder victims, all dead at the hands of a man determined to see how far he could twist the human mind. Their teamwork solved the puzzle, but the case nearly cost them their lives. Mere weeks later, they’d joined forces again for their second case together, a chilling tale of trust gone horribly wrong.

“This case couldn’t have been more different,” Leigh stated. “You’re right—it was a welcome change of pace after Bradford. Still, I’m sorry I had to cancel dinner last week. Between court and this case—” She broke off as Matt covered her hand with his.

“Don’t worry about it. I understand the job takes priority sometimes. Besides, we traded dinner for Sunday brunch, so it all worked out.”

With a quick flick of his head, he shook his untrimmed dark hair out of his eyes, briefly exposing the thick ridge of scar tissue running into his hair from his temple.

At a sudden shriek, Leigh jerked her hand free, reaching for the weapon that normally rode her hip. But even as her fingers touched soft wool instead of hard metal, her body relaxed as she quickly assessed the harmless scene across the room where a young woman had knocked over a glass of red wine.

Leigh’s gaze drifted back to Matt to find his eyes fixed on her. “What?”

He sat with his elbows braced on the table, watching her over his steepled hands. “You can’t turn it off, can you? You can’t just go out socially and let it all go. Even when a case is closed.”

Embarrassed heat flushed her cheeks at his continued examination. “It’s not like it’s a switch you throw when the clock hits five. Cops are always on duty.” Stubbornness stiffened her spine and she met his gaze head on. “Apparently you can’t turn it off either. You’re studying me like I’m one of your bones.”

“Just trying to figure you out, that’s all.” Reaching out, Matt tucked a loose strand of hair behind her ear. As his hand pulled away, he ran his fingertips along the curve of her jaw in a subtle caress. “You’re an intriguing puzzle.”

Her eyes locked with his and her stomach gave a slow, sexy roll of anticipation at the heat in his expression. “No one’s ever called me ‘intriguing’ before.”

“I like to think of you as a gift that needs to be unwrapped one layer at a—” Matt frowned as a muffled ring came from the suit jacket draped over the back of his chair. “Sorry, I need to see who’s calling.”

Leigh’s senses instantly went on alert when he froze, his gaze fixed on the name of the caller displayed on-screen. “What is it? What’s wrong?”

“I think I have to take this.”

The edge in his voice made the back of her neck prickle in alarm. “Is it one of your students?”

“No, it’s the Massachusetts State Police.”

“Calling you?” The words burst out, cutting through the buzz of conversation around them. Leigh purposely lowered her voice when several heads turned in their direction. “Why are they calling you?”

“I’m as baffled as you are.” He answered the call. “Lowell.”

Leigh leaned forward, trying to catch any trace of the other end of the conversation.

Maddeningly, Matt relaxed back in his chair even as he cocked an eyebrow at her. “Sergeant Kepler, what a surprise,” he said into the phone.

Only her white-knuckled stranglehold on the edge of the table kept Leigh from leaping to her feet to listen in on why her superior officer was calling Matt. If it was something to do with the Bradford case, he’d have surely gone through her instead.

Matt was silent for a long time as he listened, his hazel eyes fixed on her. “This request comes straight from Dr. Rowe?”

Rowe? Someone had to be dead for the medical examiner to be involved, but the remains must be in bad shape if Rowe was personally requesting Matt’s expertise.

“Whose case is it?” Matt’s eyes suddenly went arctic-cold as his casual air of relaxation dropped away. “No.” The single word was whiplash sharp. “That’s exactly what I mean. I’m not working with him. If you and Rowe want me on this case, you need to transfer it to Trooper Abbott.”

Leigh recognized that stubborn tone; she’d run headlong into it several times—Matt was digging in his heels and wasn’t about to budge.

“Actually my request is quite logical,” he continued. “Trooper Abbott and I had a rough start, but we learned how to work together. She’s familiar now with how my lab operates, and she knows my students and how we process evidence. It would waste my time to have to train a new officer.” There was a pause, and Matt’s eyes narrowed to slits. “Those are my terms, Sergeant. If you want my help on the case, have Trooper Abbott call me with the details.” He abruptly ended the call, his expression grim.

“What was that about?” Leigh demanded.

“Kepler wants me to consult on another case. There’s been a fire in Salem in one of the historical shopping districts. You probably know it—Wharf Street? The body recovered is so badly burned that Rowe needs a forensic anthropologist. He asked for me specifically.”

“That’s no surprise—you work well together. But why do you need me?”

“It’s Morrison’s case,” Matt said shortly. His open palm slapped down on the table hard enough to rattle silver and crystal. “I’ve got the right guy, don’t I? Isn’t he the Neanderthal who gives you a hard time at the detective unit?”

Leigh let out a resigned sigh. “Yes. That’s him.” She met his eyes to be sure he understood without question. “Don’t interfere, Matt. I can handle him on my own.”

“I’m sure you can. But I’m not working with him. And that’s my call to make.”

“Look, you don’t have to—”

Her phone rang.

Matt crossed his arms over his chest, his eyebrows raised in challenge. “Better get that.”

Leigh pointed an accusing finger at him. “You stay quiet. Kepler doesn’t know we’re seeing each other. He wouldn’t approve of me—”

“Fraternizing with your consultant? Too damned bad.” When her glare threatened frostbite to delicate parts of his anatomy, he mimed locking his lips and tossing the imaginary key over his shoulder.

She rolled her eyes and answered the call. “Abbott. Yes, sir.” She slipped a hand into the breast pocket of her jacket, pulled out a notepad and pen, and scribbled quickly. “Yes, I know where that is. I’ll let him know and meet him there.” She clicked off and gestured to the waitress for the check. “Kepler’s pissed.”

“He’s used to giving orders, but he’s not used to someone refusing them.” Matt pulled his jacket off the chair and shrugged into it. “Look, I understand they need help, but I’ll be damned if I’m going to work shoulder-to-shoulder with Morrison. You and I, we’ve developed a rhythm. On top of that, you value my students. If I’m going to bring them into another case, I need to know they’ll be treated well. And I know you’ll work as hard as me to keep them safe.”

“You’re still thinking about the salt marsh.”

He bristled, his shoulders pulling tight and his mouth flattening into a thin line. “I took them into the field and they were shot at. They could have been killed.”

She lightly brushed her fingertips over the back of his hand. “We’ll keep them safe. Are you bringing them in now? Or do you want to see the site on your own first?”

“I’ll bring them in now. My students are familiar with the concepts of burned remains from class, but this will take them from theory to practice. To do that properly, they need to see the remains in situ. And the extra eyes will help.” He met her gaze. “Have you ever dealt with remains like this before?”

“No.”

“Then you need to be prepared. They can be horrific, both by sight and smell.”

She grimaced. “Thanks for the warning. Are your students going to be able to handle it?”

“They’ll be fine. They held up before, didn’t they?”

“They were great.” Leigh looked out over the harbor. Suddenly the day seemed so much darker than ten minutes ago. “I was really looking forward to getting out on the Charles this afternoon,” she said. “It’s the perfect fall day for it—not too cool and not so breezy that the water would be rough and I’d tip us.”

“If I can’t keep the boat upright, then I need to put in a lot more time at the oars. I promise I’ll take you out in the scull first chance we get.” The waitress approached but before Leigh could reach for the bill, Matt slid the young woman his credit card. When Leigh objected, he simply held up a silencing finger. “My treat. You’re not going to insist on splitting everything down the middle, are you?”

“No. But you shouldn’t have to pick up the check every time we go out. You paid the last time.”

“We’ve only been out a few times, so your representative sample is too small to be statistically significant. I chose this place and it’s not cheap, so I should pick up the tab. Also, I suspect a professor’s salary beats a cop’s, so it’s not fair to stick you with the check when I picked the expensive restaurant.”

She glared at him, but remained silent.

“As I thought. You get the next one, okay?” He tucked his card back into his wallet and stood. “Rowe must be using this as another demonstration. Will he still be there when we arrive?”

Leigh rose from her chair. “I’m not sure, but I’ll find out. He may not be able to stick around that long.”

“It’s a good thing we came in two cars. You head back now; I’ll go pick up my students. We’ll be there by two-fifteen or two-thirty at the latest. They’ll hold the scene until then?”

“Yes. When remains are found in a fire, it’s officially designated a crime scene and nothing gets moved until the crime scene techs and the ME get there. The techs are probably on their way right now.”

“Then let’s go.” He circled the table to lay his hand at the small of her back as they headed for the exit. “We’ve got a scene to process.”

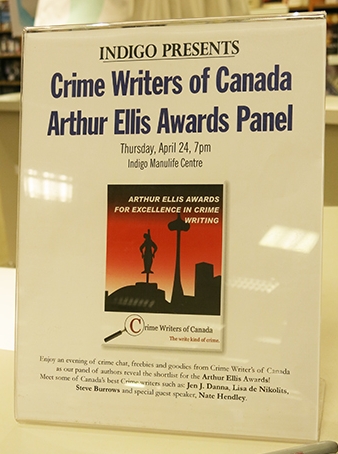

For those in the Toronto area, please join me and eleven other authors from the Crime Writers of Canada for a reading at the Manulife Indigo (55 Bloor Street West) at 7pm as part of the Arthur Ellis Awards shortlist event. More details can be found on MC Nate Hendley’s blog: http://crimestory.wordpress.com/2014/04/14/crime-writers-read-at-april-24-event-in-toronto/ Hope to see you there!

12.1%

12.1%