The Serial Podcast

/ Ann and I must have been under a rock during the late fall of last year because we both managed to miss the original airing of Serial, a new podcast from the creators of NPR's This American Life. It came to my attention after Christmas through one of my Feedly blogs and immediately intrigued me. I downloaded all 12 episodes to my iPod, but then didn’t have a chance to get to it for a couple of weeks. But once I got started, I binge-listened to the entire series—nearly 12 hours long—in three days because I was hooked.

Ann and I must have been under a rock during the late fall of last year because we both managed to miss the original airing of Serial, a new podcast from the creators of NPR's This American Life. It came to my attention after Christmas through one of my Feedly blogs and immediately intrigued me. I downloaded all 12 episodes to my iPod, but then didn’t have a chance to get to it for a couple of weeks. But once I got started, I binge-listened to the entire series—nearly 12 hours long—in three days because I was hooked.

Ann and I are big on research (HUGE understatement there) so the podcast as a whole was fascinating from a process standpoint. Journalist Sarah Koenig, a producer of This American Life, researched and hosted the program. During the course of her research, she was granted access to not only the case records and photos through the Freedom of Information Act, but also audio records from police interrogations and from both trials (the first ended in a mistrial). Many of those clips are included in the podcast, giving the listener the effect of being immersed in the case as it progressed. Ms. Koenig and her team followed old leads, rechecked stated alibis, researched 1990s architectural plans, and even drove the route driven by the suspect that day to confirm timetables. It was a very in depth analysis of a single case.

This is the true story behind the podcast: On January 13, 1999, eighteen year-old high school senior Hae Min Lee disappeared in Baltimore, Maryland. She was last seen at Woodlawn High School, but both she and her Nissan Sentra went missing after leaving the school. She was supposed to pick up her six year-old niece, but she never arrived. On February 9, her body was discovered, buried in a shallow grave in Leakin Park. She had been manually strangled.

Three weeks later, seventeen year-old Adnan Syed, the ex-boyfriend of the victim was arrested for first degree murder. The case was put together based almost solely on information gleaned from police interviews with a friend Adnan spent the afternoon with, and cell phone call records from that day. They even determined the time of death based on those call records—Hae was killed during a 21 minute interval during the afternoon. The friend, Jay Wilds, reported that Adnan had shown him Hae’s body in the trunk of her own car after strangling her in a Best Buy parking lot. He also said that he helped Adnan bury the body in Leakin Park. It was Jay that led police to Hae’s car, weeks after her death and after her body had been recovered. When the case went to trial, Adnan was convicted of first degree murder and sentenced to life in prison.

One of the great challenges of the program is the time elapsed since the events. People were asked to recall back fifteen years to events that happened in 1999. I don’t know about you, but often I have trouble remembering what happened at a specific time last week, forget about more than a decade ago. Most people had to admit that unless there was something specific that happened that day to make it stand out, memories of that time were vague and consisted of details like ‘I’d usually be in class at that time’. Adnan himself admits that he isn’t sure of his exact whereabouts that afternoon.

An interesting aspect of the podcast series was that it wasn’t recorded and then aired. They were working on later episodes as earlier ones were airing. Because of this, people who were familiar with the case or were personally involved started to contact the producers. Some of these were people who had never been contacted by police and had new information to contribute.

There were several areas of the case that certainly left the listener feeling as if they were not getting the whole story. For instance, a classmate of Adnan’s reported seeing Adnan at the library next door to the school during the 21 minute window when he was supposedly murdering Hae. If so, it's a physical impossibility that he could have crossed town to the Best Buy location and committed the murder. But did Adnan’s lawyer ever contact this classmate to bring her in to testify at either trial? She did not. Also, there is the matter of Jay’s constantly changing story to police. Each time they brought him into interview, his story changed—some aspect of where they went that afternoon appeared and then disappeared from the narrative, or the location of important actions, like Adnan showing Jay the body, changed with each telling. When Ms. Koenig drove the route Jay testified he and Adnan had taken the afternoon of the murder, the locations didn’t match the cell phone calls that took place at the same time (based on the physical location of towers pinged during each call). In my mind, this makes Jay about the most unreliable witness possible, yet the entire case was built upon his version of the story told during trial.

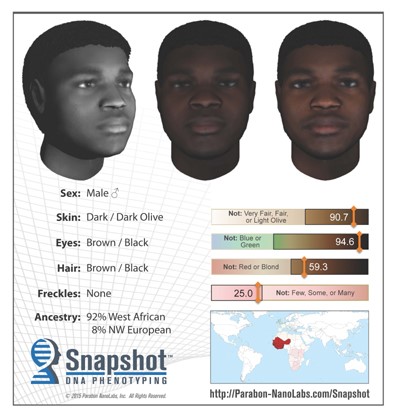

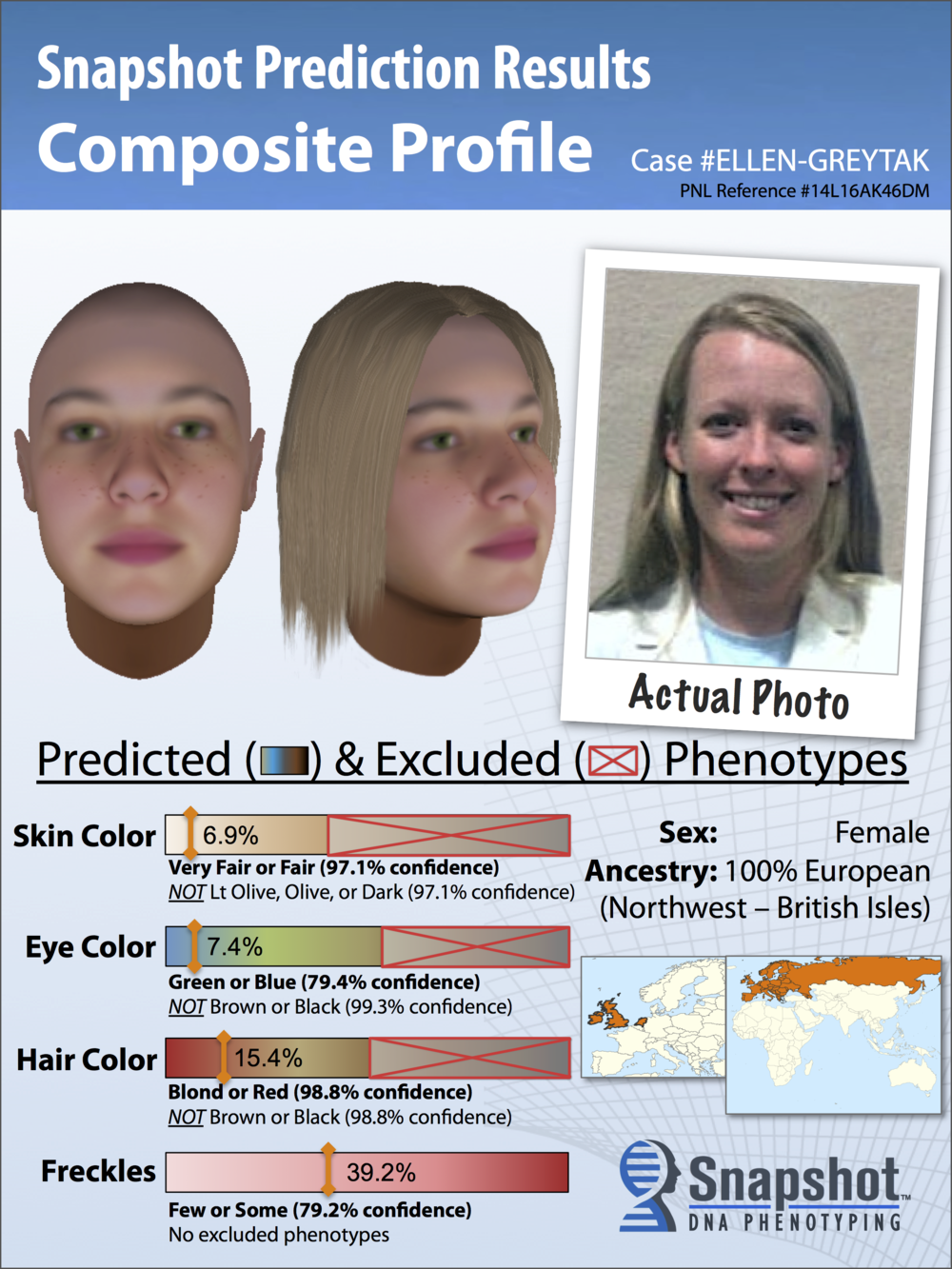

As someone who is interested in forensic science, the aspect of the case that horrified me most was the lack of evidence to support the case. The entire case rested on Jay’s testimony tied to records of cell phone calls from the afternoon. But while samples were taken from the victim, DNA testing was never done. DNA samples were taken from under the nails of a victim who died by manual strangulation while likely struggling for her life, and it was never tested for evidence of the killer's identity? Even a rape kit was done and while they tested for the presence of sperm, they never actually tested for DNA. Considering the lack of sperm, any DNA recovered would likely only belong to Hae, but it should have been tested regardless. Hairs were taken from the victim’s body, macroscopically compared to Adnan’s and found to be a mismatch, and then never pursued further. A liquor bottle was found near the body and collected. But it was never tested for DNA, something that might have pointed them toward a different killer, or confirmed the suspect they had in custody. This was 1999, well after the O.J. Simpson case; DNA testing was not new at the time. There’s no reason why this evidence was never explored.

As the podcast series ended, to the surprise of many listeners, there was no dramatic reveal or the unveiling of an alternate suspect. One of the police consultants the producers brought in described the case as ‘a mess’ and that was how it remained. There was no conclusive evidence one way or the other to exonerate Adnan or confirm his guilt. Many listeners were unhappy with the close of the podcast, but this is real life in the legal system—sometimes a case doesn’t have a neat ending tied with a bow like you see on TV.

As a result of the podcast and the attention it drew, the case is now in the hands of The Innocence Project, a group that works to exonerate innocents who have been convinced of crimes. They claim there is another suspect outside the investigation who might be responsible. Ronald Lee Moore had been in prison in Baltimore for sex crimes in 1999, but was released from prison just days before Hae disappeared. DNA samples previously collected from Moore, who killed himself in 2012, will be tested against the DNA evidence taken from the victim. Other suspects will also potentially undergo comparison DNA testing. They will also look into the possibility that Adnan’s lawyer, suffering from MS at the time (she has since passed away), botched the case. So the story of Hae Min Lee and Adnan Syed may be far from over.

Did any of you listen to the podcast? If so, what did you think?

12.1%

12.1%