When I first started this blog, I have to admit that I never thought to do book reviews. While the material I tend to talk about has more to do with forensics, science and history, this particular review came as a suggestion by one of my crit team members. Following the post on the recovery of Tsar Nicolas II and his family, Jenny and I had a discussion about The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, the narrative non-fiction retelling of Henrietta Lacks’ life and the immortal cell line, HeLa, that arose from her cervical tumor. Jenny was curious about my impressions of this book, both from the standpoint of someone who writes science for the layperson, but also as someone who has personally worked with HeLa cells. I was happy to take up her challenge.

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks was one of the top non-fiction books of 2010 and was awarded the 2011 Best Book Award by the National Academies of Science. It tells the dual-track stories of Henrietta Lacks through the 1940s and 1950s, and her family through the 1990s and early 2000s, mostly through the experiences of Henrietta’s youngest daughter, Deborah.

Henrietta was born in 1920 to poor parents in Roanoke, Virginia. After her mother died in 1924 while giving birth to her tenth child, Henrietta and her siblings moved to Clover, Virginia, where they were split up amongst different members of the family. Henrietta was raised by her grandfather, alongside David Lacks, her first cousin. Henrietta and David had their first child together when Henrietta was 14 and they later married when she was 21. They had five children together, the last being born only four months before her diagnosis.

Henrietta was diagnosed with cervical cancer at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore when she was only 31 years old. She underwent the current cancer treatments of the day, but, in the end, they proved unsuccessful. Henrietta died on October 4, 1951, a scant eight and a half months later. An autopsy performed following her death showed that her very aggressive cancer had metastasized to practically every organ in her body.

The book documents a fascinating tale of historic doctor-patient relationships and ethics. While Henrietta was unconscious, about to undergo her first treatment where radioactive radium was packed into her vagina to deliver ionizing radiation directly to her cervix, two dime-sized slices of tissue were excised from the tumour and sent to the lab of Dr. George Gey. In the 1950s, patient consent was not required for sample collection or use, so it’s doubtful that Henrietta ever knew about the extra procedure.

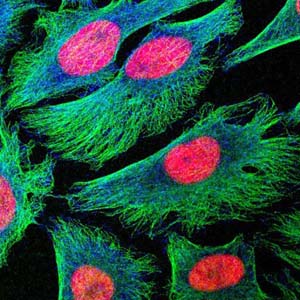

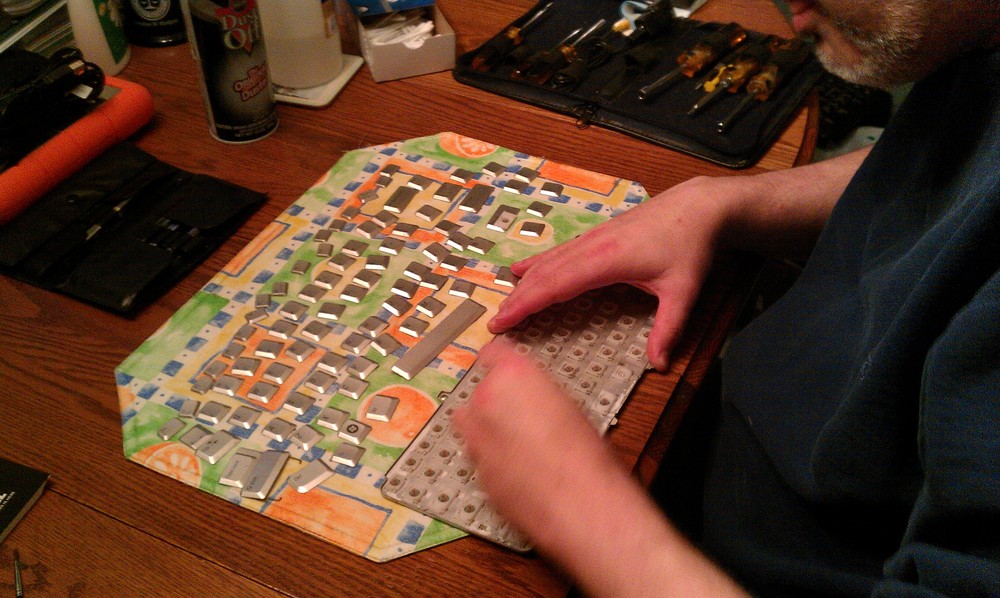

From the point of view of a scientist, this is where the book really became interesting to me. I’ve worked with HeLa cells for twenty years; they’re a staple in any cellular biology lab. More than that, from a personal research standpoint, they played a crucial role in discovering how HIV infects human T-cells, opening up the possibility of treatments and vaccines based on that information. In a scientific world where everything arrives at the lab as sterile-packed and disposable plastic, the challenges of culturing cells in 1951 were fascinating. Up to that point, no one had been able to produce an immortal human cell line (cells that can live long-term outside the host; most died in only a few days), and all cell culture was done using autoclaved glass dishes and equipment. There weren’t even any commercially available culture media; Dr. Gey created his own, and had to regularly visit slaughterhouses to collect chicken serum for his homespun recipe.

Henrietta’s cells did something that no other human tissue cultures had done before ― they not only survived the culture process, but they grew and thrived. The cell line established from these cells was called HeLa, based on the first two letters of Henrietta’s first and last names (something that would never be done today as it violates patient confidentiality). In an effort to further scientific discovery, Dr. Gey sent samples of the cells to anyone who requested them. In very short order, HeLa was a worldwide phenomenon.

12.1%

12.1%