Forensics 101: DNA Profiling for Identification

/Last week, I covered DNA as a tool for identifying remains. This week, I’m going to discuss how scientists test DNA to prove an identifying match.

DNA strands contain different regions, many of which are genes that code for essential protein products. But a very large proportion of sequences don’t code for any currently known genes. These sequences also contain short tandem repeats (STR)—small snippets of DNA that are two to six base pairs long and repeat from three to one hundred times in a row. The locations of these repetitive sections are called variable number tandem repeats (VNTR). Genetically speaking, unrelated individuals will have different numbers of repeated STR segments at known VNTR locations, but related family members will share similar numbers of repeated segments. Since human offspring share a combination of traits from both parents, the power of DNA profiling lies in analyzing numerous segments to definitively prove identification. In North America, it’s standard protocol to analyze thirteen specific locations simultaneously.

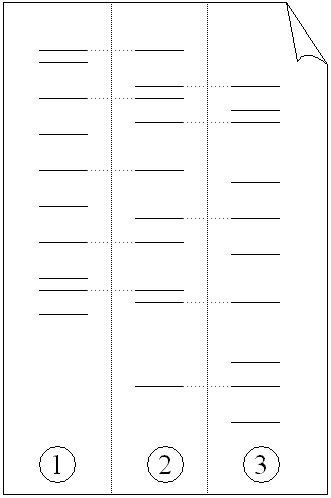

Scientists use the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to examine known VNTR locations. PCR is an assay used to amplify small amounts of specific DNA sequences so they can be visualized later on a gel (we’ll look at PCR in more detail in a future Forensics 101 post). The picture above illustrates typical PCR results. In this case, a gel shows the difference in length of the D1S80 VNTR location of six unrelated individuals, flanked on each side by a marker of known size. As you can see, the pattern for each individual subject is different in each vertical lane.

An example of DNA profiling between a father (1), mother (3) and child (2).

There are two types of matches in DNA profiling—identity and inheritance. In identity matching, the unknown sample is tested against a known individual’s DNA. If the two samples match exactly, then the unknown person is identified as the known donor. In inheritance matching, the unknown sample is tested against a sample drawn from a potential family member. If parents are used as donors, then each band in the unknown sample must match with one of the two parents. If a more distant relation is used, then degrees of relatedness are calculated into the expected results.

The bottom line of this testing is that the unknown sample must be tested against a sample (blood, hair, tissue etc.) of known origin. In the case of Richard III’s ancestors, separated by five centuries from the king himself, genomic DNA profiling as described above simply wouldn’t be feasible due to the number of generations separating Richard III and his current ancestors. But when this same method is applied to mitochondrial DNA, because of the consistency of maternal transmission, identical or near identical results are expected between family members, even those separated by multiple generations.

Next week, we’ll look at the historical details surrounding the Princes in the Tower, the young boys Richard III is accused of murdering. Nearly one hundred years after their disappearance, bones were recovered at the Tower of London. But where they of the missing princes? See you next week to find out…

Photo credit: PaleWhaleGale and Magnus Manske

24.9%

24.9%