How to Identify a Suspect… By His Microbes?

/ There are many established ways to identify a criminal suspect after the fact—DNA or fingerprints, for example (but not bite marks). But in 2010, a theory was introduced that a person could be identified by the bacteria they carried on their skin. The idea is that each person’s specific mix of microbes (called their ‘microbiome’ in scientific circles) is so individual that it could uniquely identify them.

There are many established ways to identify a criminal suspect after the fact—DNA or fingerprints, for example (but not bite marks). But in 2010, a theory was introduced that a person could be identified by the bacteria they carried on their skin. The idea is that each person’s specific mix of microbes (called their ‘microbiome’ in scientific circles) is so individual that it could uniquely identify them.

Let’s back up a step because some of you are probably thinking Yeeeccccchhhhhhhh! I’m carrying WHAT on me? Actually, the bacteria that we always carry on us are an important part of our biological stability and are genuinely good for us. While the microbes that live on us make up only approximately three to five pounds of our total body mass, because they are so much smaller than our somatic cells, they actually outnumber our cells by approximately 10:1. In fact, there are enough bacteria that live on us that if we could collect them all, they’d fill a large soup can.

We’re born essentially microbe free, but breastfeeding is the first important transfer of good gut bacteria to newborns. By the time we are adults, it’s estimated that well over 500 species of bacteria live in our gut. These are symbiotic bacteria, meaning they live off us, but we reap the benefits of them in return. We provide a food source for them, but they help us digest our food and better obtain nutrients from our meals. Gut bacteria also help maintain our mucosal immune system making us healthier. Just look to your nearest grocery story or pharmacy for probiotics or probiotic yogurt sold to supplement your natural gut flora. This is exactly why it’s become a significant industry in recent years.

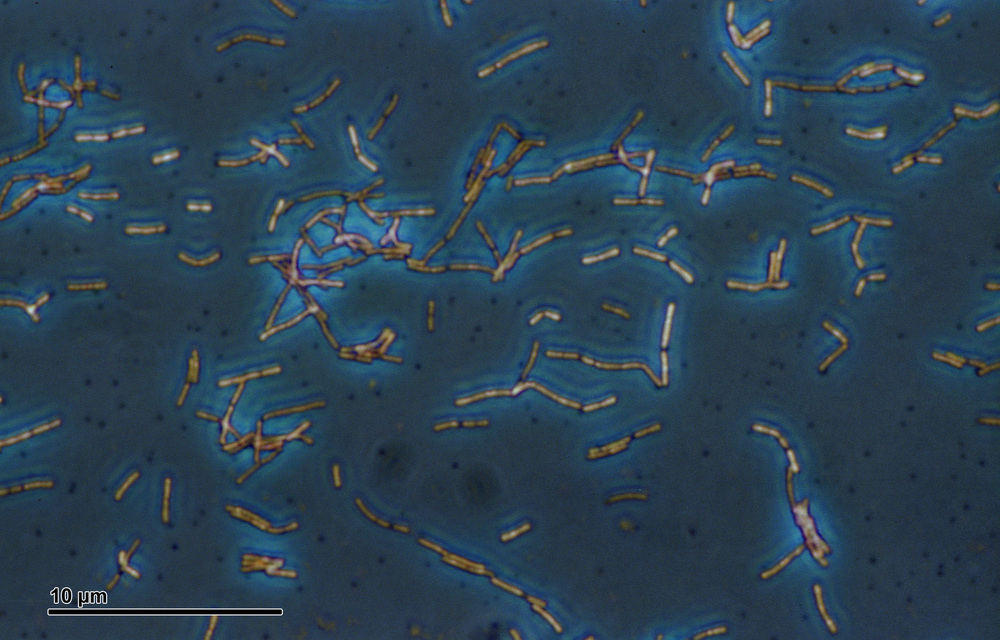

But what about the bacteria that live on your skin? The skin is the body’s largest organ and is our first line of defense against pathogenic invaders. But we’re not alone in the fight—a diverse panorama of bacterial flora live on our skin. Some bacteria help protect us by producing antimicrobials to kill pathogenic bacteria, while others work with our cells, actively using substances we produce to kill invaders. Because the skin is a varied environment with a multitude of cells, glands, follicles, natural moisture levels, and layers of epidermis, we are host to a wide range of bacteria that each live in their own preferred environments. It is these bacteria that give us a unique microbial fingerprint.

This fingerprint is analyzed by identifying the DNA sequences of the bacteria an individual carries. Most individuals host a similar complement of types of bacteria, but it is the relative amounts of these hundreds of strains that constitutes a fingerprint. So each time you touch an object and leave an oil and amino acid slurry fingerprint, you also leave a microbial fingerprint behind. The more commonly used the item, the stronger the microbial fingerprint, with cell phones, keyboards, and shoes bearing the strongest signal. A theory exists that since we leave a bacterial trail behind as we move through the environment, it might be possible to trace a suspect by the trail left by his shoes. It’s even been suggested that a forensic trail left at a crime scene might remain intact for up to two weeks, a very significant period of time in any investigation.

Much study must be done before an individual’s microbes could be used as a forensic tool during a criminal investigation. Previous experiments have been done on groups between two and one hundred and twenty individuals, so the power of this technique can only lie in a specificity that could eliminate millions of individuals to match the power of DNA profiling or fingerprinting. But it’s an intriguing possibility and one that can only expand as studies on the human microbiome, a relatively new field, expands into new and exciting territory.

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

12.1%

12.1%