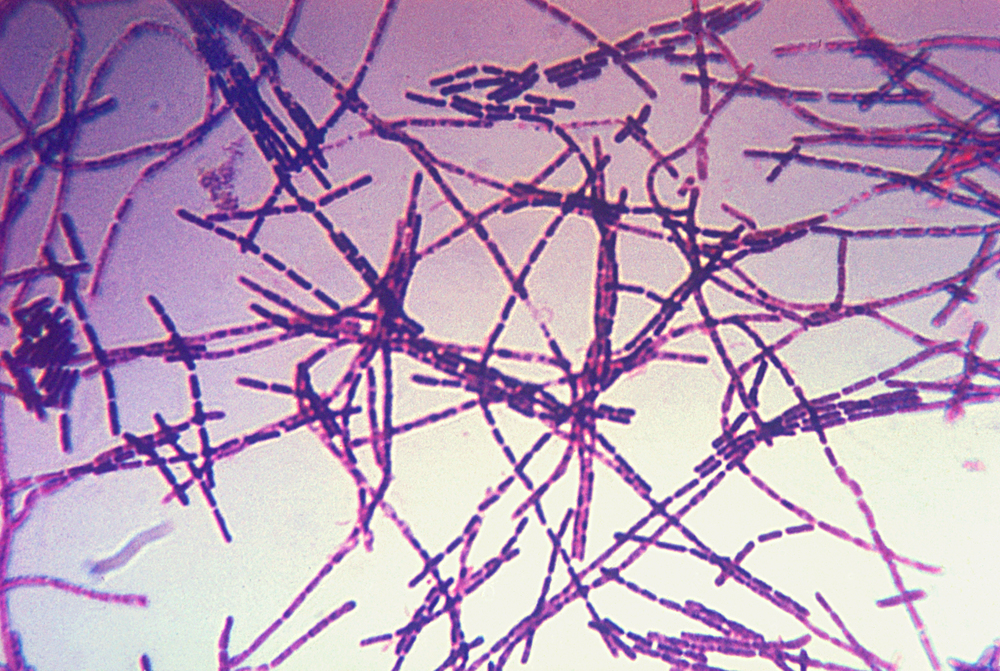

Biosecurity Incidents In Top U.S. Labs—What, Me Worry? Anthrax Edition

/

Today we’re continuing on with our series on laboratory biosafety and how it’s gone wrong lately in places you would think would be immune to such incidents. But it just goes to show human error can trump every precaution you put in place and that hopefully your people would follow to the letter. Especially when lives are on the line. But not so much, apparently…

In July of 2014, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) held a press conference to discuss two different incidents that had taken place the previous month. We’re going to showcase one incident this week and one next week.

The first incident involved a CDC lab preparing extracts from anthrax, a biosafety level III (BSL III) pathogen. Their usual protocol involved chemically deactivating the pathogen for 24 hours, but they learned of a new protocol that only required a 10 minute deactivation. Now, this protocol was not for anthrax, but was instead for Brucella, another BSL III pathogen. However, they elected to try this new protocol on anthrax. This method also included a double check—after the pathogen is deactivated, some of it is plated onto agar plates and incubated for 48 hours to ensure there is no growth, and all the pathogen is dead. The CDC first attempted this protocol in June of 2014, sampling the extract to agar plates after 10 minutes, but leaving the rest for the full 24 hours.

However, due to a misunderstanding during a phone conversation and a lack of follow-up with the actual printed protocol, the scientist responsible only left the agar plates for 24 hours post deactivation, at which time, the plates were determined to have no growth. The scientist intended to autoclave the plates and discard them that day, however he could not open the autoclave door, so the plates were returned to the incubator. At this time, the anthrax incubated for 24 hours was distributed as deactivated pathogen to biosafety level II (BSL II) labs. Eight days later, the agar plates were removed from the incubator for disposal and, to their surprise, anthrax growth was observed. Scientists realized the 10 minute procedure was not sufficient to kill anthrax, but were unsure if the 24 hour procedure (from which anthrax had been sent out to BSL II labs and their lower level of containment) was sufficient. At that point, it had to be considered that they had a breach in biosafety containment and all the labs had to be completely decontaminated. Later tests showed that the 24 hour procedure was sufficient to kill most of the anthrax, but not all. As a result, while it was unlikely that infection would occur, it was not impossible.

Upon closer examination, there were a number of issues that led up to this incident:

- Use of unapproved techniques—there were several related to filtering of the extract, but this also included observing the plates for sterility at 24 hours instead of the required 48 hours.

- Transfer of material not confirmed to be inactive—based on the error made in point 1, this also involved a lack of written protocol of what was required to ensure that pathogens were truly deactivated.

- Use of pathogenic strains of anthrax to test out a new protocol when non-pathogenic strains would have revealed the same conclusion with none of the risk. This was an extremely unwise decision.

- Inadequate knowledge of peer-reviewed literature by both the laboratory scientist and his supervisor—papers already existed outlining that this method was not sufficient for absolute sterility of infectious anthrax.

- Lack of standard operating procedures to document pathogen deactivation.

Fortunately, no staff member ever presented with symptoms of anthrax. But the laboratory in question was closed pending a number of assessments, the establishment of new procedures, and until remedial action was taken with the staff involved. This was not a shining moment for the CDC, the institution we scientists like to consider the gold standard in biosafety. This is the group you call when something goes wrong and this is what their own people are doing?

In the last month, a new anthrax story surfaced concerning an Army lab at the Dugway Proving Ground in Utah. It creates anthrax test kits and sends them out to numerous laboratories for local testing. Contained in the kit is a radiation-killed sample of anthrax to use as a positive control for testing. However, in May, a Maryland biotech company identified that live anthrax was present in the samples. Upon closer inspection, it appears the samples were not sufficiently treated to kill all the spores. The test kits were packaged and sent out, many by regular FedEx delivery, to 69 labs around the United States, but also in Canada, Britain, Australia and South Korea. The CDC has confirmed that all kits shipped between 2004 and 2015 contained live anthrax.

Even more disturbing information surfaced this past week. It appears that from 2007 onwards, the lab was aware that their deactivation process (chemical deactivation at the time, and later irradiation) was not sufficient to kill all the anthrax, but they ignored the issue. At the time, federal regulators at the Office of the Inspector General were aware and recommended further investigation and potential enforcement action, however nothing was ever done. Furthermore, the information was never reported to Congress—the group responsible for oversight of this lab—so they were completely unaware of the situation. No laboratory workers have shown symptoms of anthrax; however 31 workers are receiving antibiotics as a precaution.

Next week, we’ll be returning the CDC as we discuss a serious mishap concerning a highly pathogenic strain of influenza.

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

12.1%

12.1%