Forensics 101: Sexing an Unidentified Victim Based on Skeletal Markers – The Skull

/Ideally, when human remains are found, the whole body is recovered. If so, multiple skeletal components are used when determining the sex of the victim. Unfortunately, it is common that only partial remains are discovered. In the last Forensics 101 post, I discussed how to sex a skeleton based solely on the pelvis, which is considered the most reliable method of sexing adult remains. But what if only the skull is recovered? Luckily, a forensic anthropologist has a few tricks of up his sleeve and can tell quite a bit from a human skull.

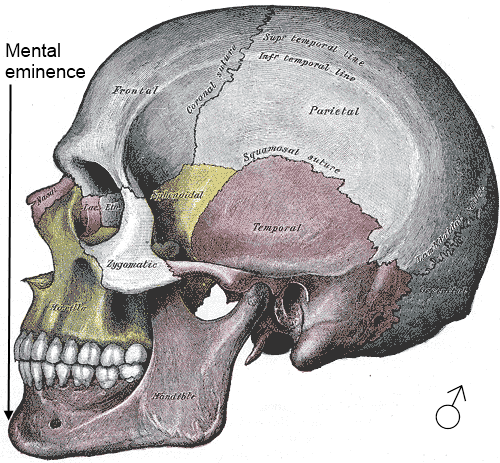

I have included several photos to illustrate the relevant skeletal markers used in sexing a skull. Since all the available skeletal specimens were female, I’m using an illustration from Gray’s Anatomy to include details of the male skull.

- Mastoid process ― This is the point of attachment for the muscles in the neck and torso that allow you to turn your head. As male musculature tends to be more robust than female musculature, the male mastoid process tends to be larger in size.

- Supraorbital ridge/glabella ― This area is located between the eyebrows, just above the nasal aperture. In females, the glabella tends to be flat, with no prominence. In males, there can be a slight to a heavy prominence.

- Mental eminence ― In layman’s terms, this is the chin. In females, this area tends to be flat, or with only a small projection. In males, the projection can be mid-range to quite large.

- Nuchal crest ― This is the attachment point for the nuchal ligament and nuchal musculature, connecting the head to the spine and assisting in its support. Less pronounced in females, it can form a significant projection in males, sometimes even taking the form of a bony hook.

Besides contributing to sex determination, the skull is also very useful in determining race as well as the age of the victim at the time of death. In the next Forensics 101 post, we’ll look at how to determine age of a victim based on skeletal remains.

Thanks to the McMaster University Department of Anatomy for providing skeletal specimens.

12.1%

12.1%