Throughout the month of February, we’re going to be previewing TWO PARTS BLOODY MURDER, which releases on February 18th in both hardcover and eBook.

Throughout the month of February, we’re going to be previewing TWO PARTS BLOODY MURDER, which releases on February 18th in both hardcover and eBook.

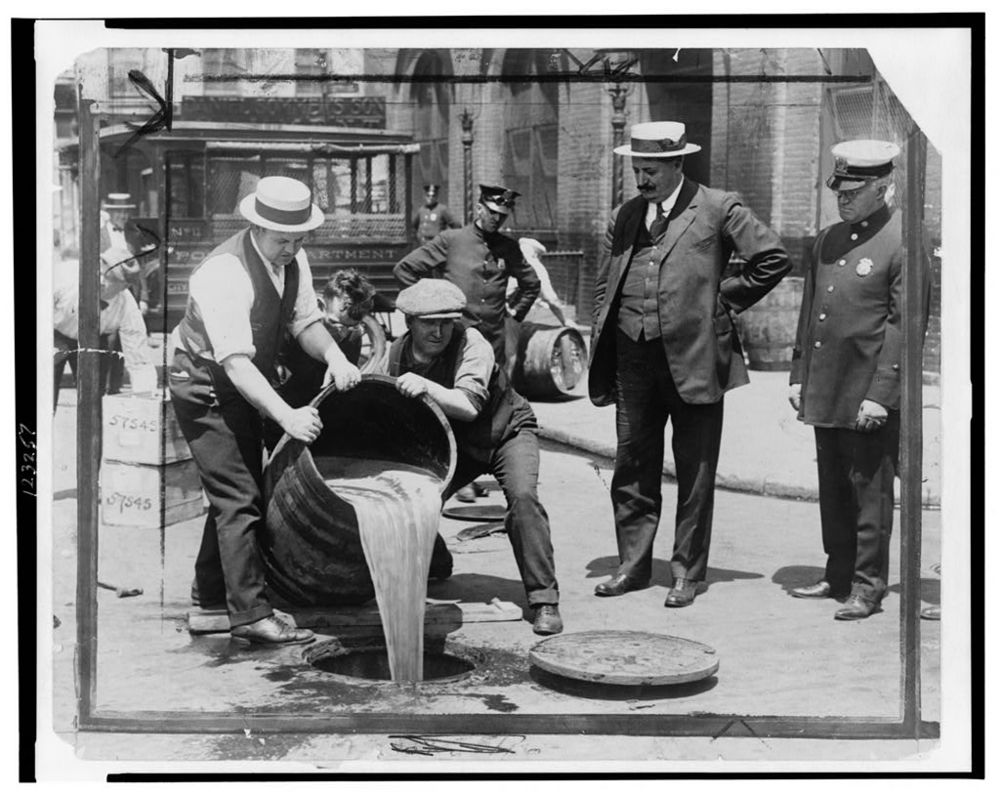

The history behind the story is fascinating. While set in modern day, the case is unexpectedly thrown against the backdrop of U.S. Prohibition which took place during the 1920s and 1930s. Prohibition was not strictly an American concept—it has, in fact, been enforced in many countries from Asia, Europe, South America, and Oceania. In North America, both the U.S. and Canada had Prohibition, but, Canada’s was never a national law. Instead, provinces instituted their own short-lived laws, and Prohibition was a thing of the past for Canada by the early 1920s—just about the time the U.S. was getting started. As a result, Canada became one of the pipelines of that fulfilled black-market needs.

Since most North Americans only consider Prohibition to be an American phenomenon, and since that’s the background used for TWO PARTS BLOODY MURDER, that’s what we’re solely going to discuss over the next few weeks.

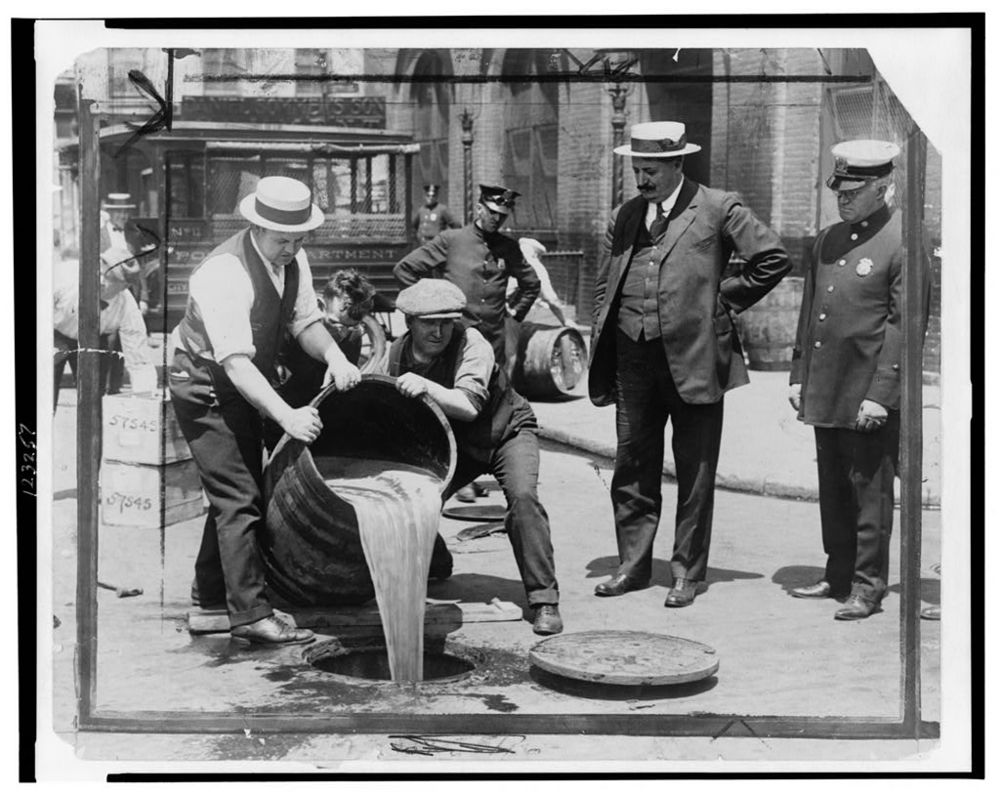

What is Prohibition in the larger sense? Opposed to the commonly held belief, Prohibition did not outlaw the consumption of alcohol. Instead, Prohibition made it illegal to produce, store, transport or sell alcohol to the consumer, who was then legally free to drink it.

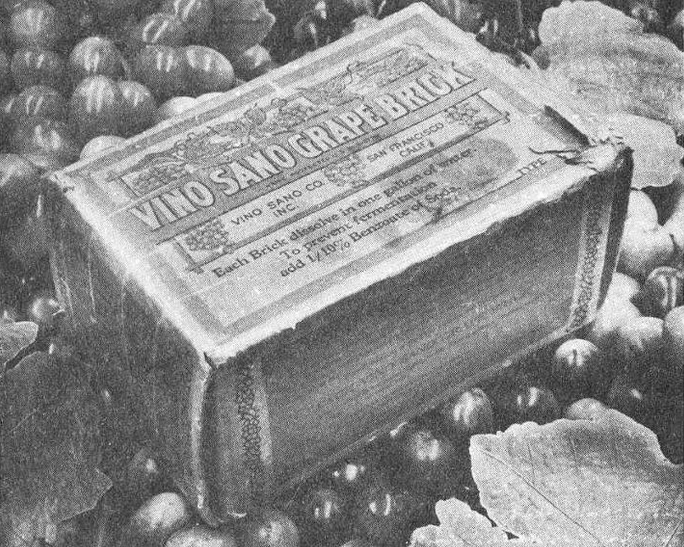

Was it a universal law? There were exceptions to the law because alcohols were still used in some manufacturing processes (including dyes and fuels) and for religious rituals, while poisonous denatured or wood alcohol was used in scientific research.

Why was Prohibition needed? Prohibition was a concept that came out of the Temperance movement in the U.S. which began in the 1820s. In its original form, temperance promoted moderation in alcohol consumption, especially in hard spirits, and while they encouraged abstinence from alcohol (called teetotalism), it was not a requirement. But as the years progressed, the movement shifted towards total abstinence, backed by legislation as required. The movement was mostly led by women, who along with their children, had suffered at the hands of husbands who drank away their paychecks or abused their families while drunk. They also claimed that ‘demon alcohol’ was responsible for poverty and destitution, crime, and ill health.

When did Prohibition start? Several states made early attempts at legislation. Maine was the first state to ban alcohol in 1851 and it later served as a model for several other states. During the American Civil War, both the North and the South needed duty from alcohol sales to finance the war effort, so many states repealed those laws. Following, the Civil War, the temperance movement intensified, especially after the formation of the Anti-Saloon League.

How was Prohibition legislated? Prohibition became federal law in the United States in 1920, mandated by the 18th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. The legislation itself was called the Volstead Act. We’ll look into that in more detail next week as we also look into law enforcement’s challenge to enforce it.

How was Prohibition ended? Despite all the good intentions that started Prohibition, it proved to be immensely unpopular and essentially impossible to enforce. On top of that, crime rates and urban violence soared as the Mob and other gangsters used the black-market to fill the gap previously filled by legal manufacturing. Corruption within law enforcement proved to be an ongoing problem that may have been the final nail in Prohibition’s coffin. According to Chicago’s Chief of Police, an estimated 60% of his officers took part in the illegal bootlegging of alcohol. As a result, the 21st Amendment to the Constitution to the United States repealed the 18th Amendment. To this day, the 18th Amendment remains the only constitutional amendment to have ever been repealed.

Over the next few weeks, we’re going highlight short snippets of TWO PARTS BLOODY MURDER that illustrate some of the history we’re discussing. The following excerpt occurs when Leigh enters Matt’s lab at Boston University to find medical examiner Dr. Edward Rowe discussing the case with Matt. To the surprise of the team, Rowe turns out to be a local history buff and he becomes their guide to the 1930s:

Leigh crossed the room toward them. “And once again, I didn’t expect to see you. You’re like a bad penny—you keep turning up,” she said to Rowe, returning his grin as he set the clavicle back into place.

“I’m playing hooky.” Rowe raised a gloved finger to his lips. “Don’t tell.” He waggled bushy eyebrows at her and turned back to the remains.

“Wild horses couldn’t drag it from me. Actually, I’m glad you’re here so we can pick your brain. Does the term ‘blue ruin’ mean anything to you?”

Rowe straightened, the T-12 vertebra cupped in his left hand. “Sure does, especially if you mean in reference to the speakeasy. It’s an old slang term for what was commonly known in the twenties and thirties as ‘bathtub gin.’”

“Bathtub gin? Isn’t that a slang term in itself?”

“Not as much as you’d think. Bathtub gin was basically homemade booze. In its simplest, non-distilled form, it only needed a day or two to age, so you could make it and drink it fairly quickly. It’s a method called ‘cold compounding’: mix grain spirits with something for flavor, like juniper berries—thus the reference to gin—and maybe something as exotic as citrus peel if you had it, and then dilute it out by adding tap water. But they made it in such large containers, they couldn’t fit the bottle under the kitchen faucet, so they’d use the bathtub instead. Thus, ‘bathtub gin.’ If you had the equipment, you could distill this same mixture, which was much safer. If there was any methanol contamination in the mix, it evaporated first during distillation.”

“It sounds awful.” Leigh wrinkled her nose in disgust.

“It was awful, but it could get worse. For many, if they couldn’t get their hands on grain spirits, they used denatured alcohol.”

Now it was Matt’s turn to wince. “That could be a death sentence.”

“For many it was. Or you could get off lightly and just go blind.”

“People were that desperate for alcohol they’d drink poison?” Leigh asked.

“A lot of them didn’t know they were drinking poison. But many of them knew they were taking their chances and did it anyway. It’s hard to describe the desperation of people back then, especially during the Depression. The chance to escape the misery of their daily lives, even if only for a little while, was simply too big a temptation. The worst of it was the Feds got involved in it too.”

“How?”

“They knew what was going on. Distilling alcohol was illegal under the Volstead Act but it happened anyway. But because alcohol was needed for scientific research and the production of dyes and fuels, the Feds knowingly poisoned some of that alcohol to discourage it from being used for human consumption. People drank it anyway and died by the tens of thousands. And then the Feds had the nerve to label them ‘deliberate suicides.’”

“Unbelievable,” Matt muttered.

“Believe it.” Rowe set down the vertebra and pulled off his gloves. “It was a different time back then and the Feds had the power to do whatever they pretty much wanted.”

See you next week for our next bit of history—law enforcement during Prohibition.

Photo credit: Library of Congress

2.1%

2.1%