What Makes a Good Critique Team Member?

/

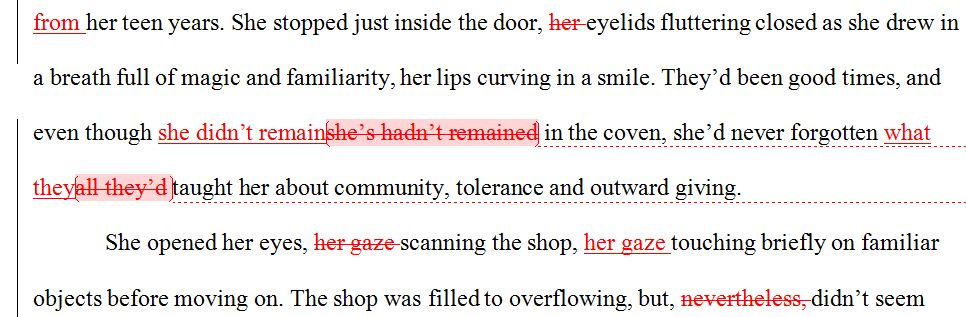

This past Friday, I had the great pleasure of sending the manuscript for A FLAME IN THE WIND OF DEATH to my critique team. After months of work, and especially after 2 or 3 weeks where Ann and I killed ourselves to get it ready on schedule, we’re finally enjoying a short break while someone else carries the ball.

Ann and I were very lucky that we had a great group of beta readers for DEAD, WITHOUT A STONE TO TELL IT. But from that group, we narrowed it down to a smaller group that we consider our core critique team. So, what makes up a good critique team?

- Everyone brings something different to the table: Our team is made up of an editor, two authors and a reader. Sharon, our editor, has a sharp eye for language, and never fails to catch our small errors while still seeing the big picture. Margaret and Jen are each excellent authors in their own right. As such, they’re skilled in storytelling and identifying strengths and weakness in plot or characterization. Lisa is a reader, but, more than that, she’s our technical advisor and our logical thinker. A 20-year veteran of a northern California fire department, she’s been essential to us during the writing of FLAME. But she was just as essential through DEAD because she knows law enforcement officers almost as well as firefighters, and was always able to catch our logical missteps.

- The ability to give constructive criticism: This is actually a real skill. To give constructive criticism, team members not only need to be able to pinpoint what isn’t working for them, but also why it doesn’t, and then give suggestions about how to fix it. All four team members are great at this—this situation doesn’t make sense because of this, so why don’t you try that instead? They see the issues that we don’t simply because we’re too close to the story.

- Willingness to help out on a moment’s notice and stick to a schedule: I try not to call on my team at a moment’s notice, but regardless of that intention, I’ve done it to them twice in the past. To make it worse, one of those times was two weeks before Christmas 2011 as we were sprinting to complete an edit our publisher requested. Each time, they’ve all willingly jumped in and stayed on schedule, even as Christmas loomed large. I always try to keep them in the loop, giving them at least a month’s notice and then setting a hard deadline two weeks before, but sometimes that’s not always possible. Luckily, this time, I was able to do that for them.

How important is a good critique team? They’re absolutely crucial to our writing process. Some authors have only one critique partner, but I like having a team to work with us because they each help out in different ways. Put them together and their feedback is essential to the production of a solid manuscript that I then feel confident sending out to professional editors.

For other writers out there, do you work with a crit partner or team? And do you feel their input is paramount to the success of your manuscript?

12.1%

12.1%