Canine Highlight – World War I’s Sergeant Stubby

/We’re starting a new type of post this week: the canine highlight. We’d like to bring to your attention some particularly outstanding working dogs who have shown as much courage as their human counterparts, saved lives, and significantly affected those around them in the most positive of ways. This week, we bring you the amazing tale of Sergeant Stubby.

In last week’s post, we talked about working dogs through the ages. We mentioned the working dogs of World War I, concentrating on the medical aide dogs that were sent out onto the battlefields after the cessation of fighting to bring supplies to those in need. But there were other dogs as well who joined the cause—and one of those was Sergeant Stubby.

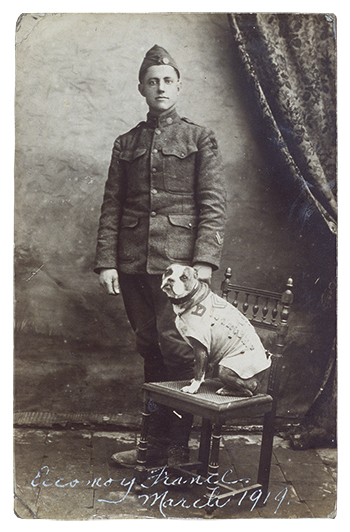

When a young bull or Boston terrier mixed breed dog wandered onto Yale University campus and into the training grounds of the 102nd Regiment, 26th Infantry Division, Corporal John Robert Conroy took a liking to the little mutt. He started feeding the stray and even let him sleep in the barracks. Eventually, Stubby became the Division mascot, spending so much time with the men that he learned all the marching maneuvers, and even was trained by Conroy to salute with his paw.

When the 26th Infantry Division was shipped out to France aboard the SS Minnesota, Conroy smuggled Stubby aboard, and then tried to keep his presence hidden. Eventually, the dog was discovered by the commanding officer. However, Stubby won the officer’s goodwill by saluting him, and was then allowed to stay with the Division openly.

Stubby accompanied the 26th to the Western Front in France, where he proved to be an invaluable part of the unit. After nearly being killed early on by mustard gas, he became adept at stiffing it out early and running up and down the trenches barking at the men to put on their gas masks before going to hide himself. His extremely sensitive hearing was also a boon—he could hear incoming shells long before the men and warned them to take cover, and he could hear the approach of advancing German foot soldiers and warned the sentries of the imminent attack. He was also known to scour the territory of “No Man’s Land” following any fighting, looking for fallen Allied soldiers in need of rescue. Stories of the time reported that he would only respond to the English language, thus avoiding the wounded Germans altogether. His actions in the unit saved countless lives.

During the Meuse-Argonne campaign in 1918, Stubby discovered a German spy in their midst, mapping the Allied trenches to take the intelligence back to the Central Powers forces (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria). When the spy tried to make a run for it, Stubby went after him and brought him down, and then clamped his jaws around the man’s rear end until soldiers from his own unit came to take the spy into custody. The unit’s commanding officer was so impressed with his performance that the dog was battlefield promoted to the rank of sergeant. This meant that he actually outranked his owner, Corporal Conroy.

Stubby took part in seventeen battles and four major offensives on the Western Front, and was the recipient of the following medals and devices for his service in battle: 3 Service Stripes, Yankee Division YD Patch, French Medal Battle of Verdun, 1st Annual American Legion Convention Medal, New Haven WW1 Veterans Medal, Republic of France Grande War Medal, St Mihiel Campaign Medal, Purple Heart, Chateau Thierry Campaign Medal, and the 6th Annual American Legion Convention.

Following the war, Stubby went to Georgetown University with Conroy while he studied to become a lawyer. While he was there, Stubby became the mascot of the football team and was infamous for coming out during the halftime break and pushing a football around the field with his nose to the delight of the crowds. He was inducted into the American Legion, marching in all their parades, and even met Presidents Wilson, Coolidge and Harding at the White House.

You can still see Sergeant Stubby today. Following his death in 1926 at approximately ten years of age, he was taxidermied by Conroy and gifted to the Smithsonian in 1956. He is now part of one of their World War I exhibits at the National Museum of American History. His WWI uniform, complete with all his medals, is on display at the Hartford State Armory.

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons and Smithsonian National Museum of National History

32.0%

32.0%