A New Method to Determine Time Since Death?

/There are two significant challenges in any criminal investigation involving badly decomposed or skeletonized remains: who is the victim and when did he or she die?

In the Abbott and Lowell Forensic Mysteries, we’ve dealt with the time since death, or post mortem interval (PMI), issue a few times. In the very first book in the series, DEAD, WITHOUT A STONE TO TELL IT, Trooper Leigh Abbott and Dr. Matt Lowell nearly come to blows when Leigh needs a time since death estimate so she can start looking at missing persons reports, and Matt, a quintessential scientist, refuses to guess when he’s lacking sufficient data. In TWO PARTS BLOODY MURDER, when a skeleton is found immured behind a brick wall, it is Dr. Edward Rowe and his knowledge of history that dates the skeleton. But in LAMENT THE COMMON BONES (out two weeks today!), when a murder victim is found hanging in a forensic anthropology lab, it’s impossible for Matt to estimate the PMI because he’s missing the usual markers—tissue decomposition or bone weathering. The best he can do is to provide a minimum PMI based on the time required to prepare the bones. The maximum can be determined by the last time the victim was seen alive, but that only provides at best a detrimentally large window for a murder investigation. However, a small side storyline involves Dr. Trevor Sharpe, Matt’s scientific arch nemesis, and why Matt hates him so much. In the end, it all has to do with PMI estimates and the extent some researchers will go to in their search for scientific glory.

In the real world, a lack of understanding of PMI started the criminal investigative aspect of forensic anthropology as we currently know it when Dr. Bill Bass misjudged the age of a corpse by over a century (see the fascinating story of Colonel William Shy). As a result, he started the University of Tennessee Forensic Anthropology Research Facility (nicknamed the ‘Body Farm’) in 1981. Since then, research into decomposition in different locations and during different seasons, scavenging, the affect of trauma, entomology, and many, many other aspects of the process of death have elucidated scientific details that have greatly improved criminal investigations.

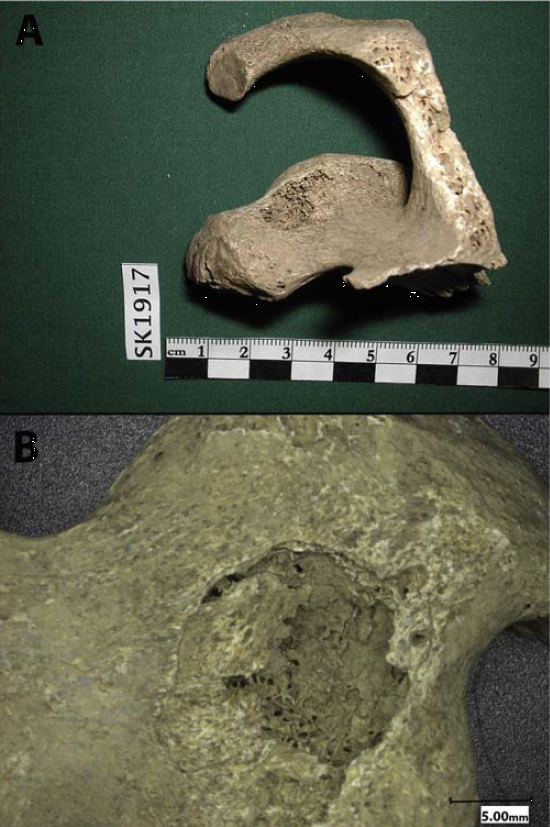

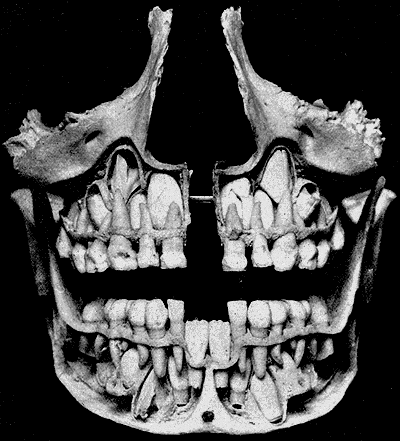

However, definitive estimates of PMI continue to elude scientists in certain cases, especially those involving skeletonized remains. Without definitive tissue markers, or obvious weathering clues, some estimates around PMI can span months or even years, greatly complicating any criminal investigation. Enter Lincoln Memorial University, Dr. Beatrix Dudzik, and her new project to study bone marrow, the protected inner contents of bones that produce both red and white blood cells. They hope to use the decomposition of lipids within the bone marrow to estimate the time elapsed since death. They are basing their research on a study by Paul Wood and Natalie Shirley where PMI was reliably determined based on skeletal muscle decomposition and the biochemical breakdown products produced up to a year after death. Knowing the difficulties involved in skeletal remains, Dudzik would like to translate a similar breakdown process to bone marrow.

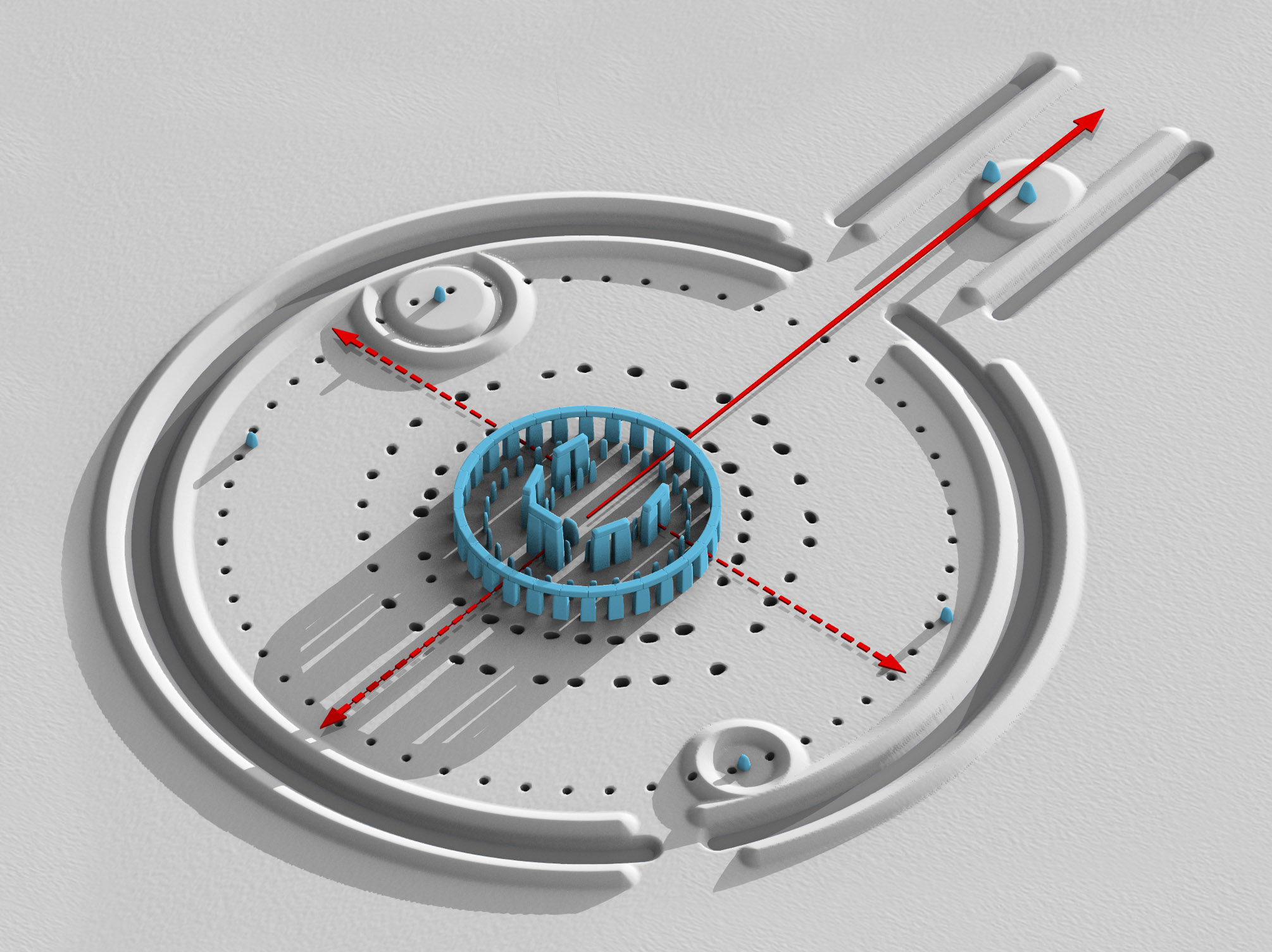

The study will take place at the Body Farm, using twenty donor cadavers over a two-year time period, as well as samples already in the Body Farm’s bone collection with known PMI’s from one to thirty years. The study, which will start in January 2018, will study three types of bones specifically—the calcaneus from the ankle, the tibia from the lower leg, and a vertebrae—as well as teeth to test for lipid breakdown products.

The group hopes that the initial two-year study will produce data allowing for an extension and additional research to better understand this complicated process.

LAMENT THE COMMON BONES releases two weeks from today and we’ve got a couple of buy links already up for readers who like instant gratification and want their copy waiting for them when they wake up on November 21st. So for e-book readers, we have the following links:

Kindle: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B077721M4V/

Kobo: https://www.kobo.com/ca/en/ebook/lament-the-common-bones

Newsletter readers are getting an advanced sneak peek at the first three chapters of the book today, but come back to the blog next week for a chance to see the exciting opening chapters early!

2.1%

2.1%