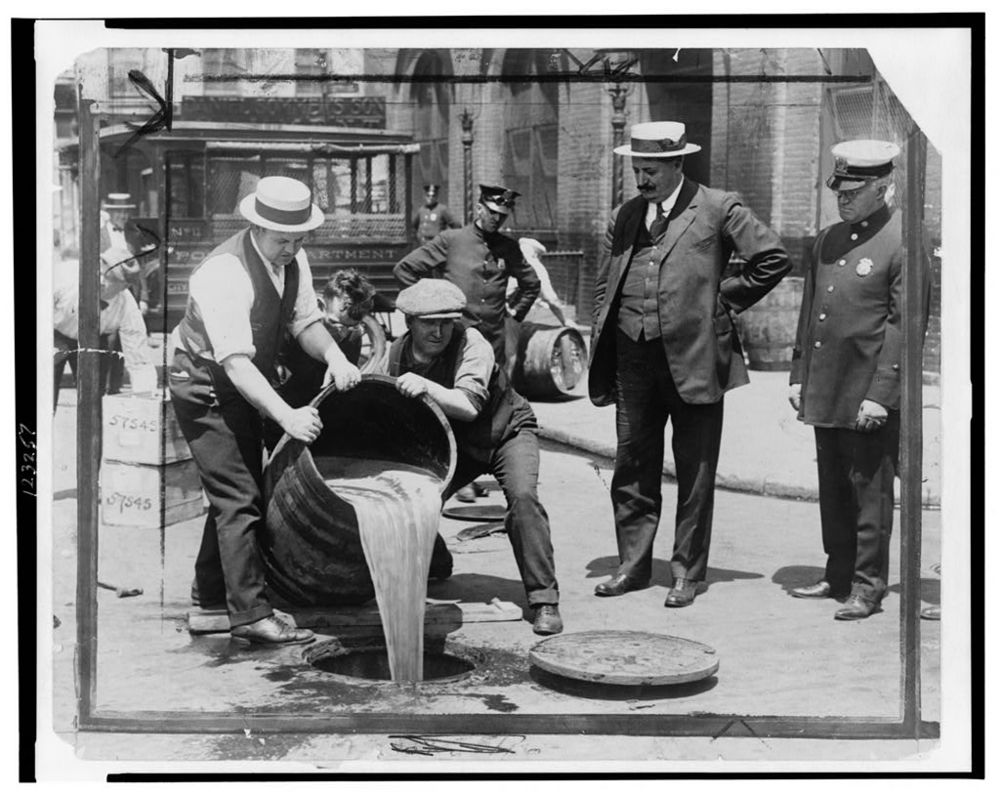

Over the past few weeks, we’ve been highlighting some of the history behind TWO PARTS BLOODY MURDER since it plays a major part in both the case and it’s resolution. So far we’ve talked about why Prohibition started, and the challenges of enforcing the law when not only the criminals but also law enforcement were breaking the law. This week, we want to talk about speakeasies and the culture that flourished around them.

By the strictest definition of the word, a speakeasy was an establishment that illegally sold alcohol during Prohibition. But in reality, that term could apply to anything from the most basic gin joint that sold only the hardest and harshest (including potentially poisonous) of drinks, to the snazziest nightclubs featuring high profile performers. These were permanent establishments, often controlled directly by the mobs, so while competition was fierce, secrecy was key. Unless local law enforcement was already on the take, it was crucial that they were kept in the dark to prevent clubs from being raided. This would not only mean the loss of whatever alcohol was on site, but also the loss of the location as well, all of which added up to a huge financial disaster and jail sentences for anyone connected with the operation.

Many of these establishments tried to hide under the guise of legitimate businesses like cafés, or literally went underground into basements or into upper floors of buildings. Word of mouth was the main form of advertisement, with entrance to the establishment often depending on a whispered password to the goon guarding the front door.

Entertainment at a speakeasy (beside the alcohol) often came in the form of floorshows, especially jazz bands. Jazz was a relatively new musical form at the time and was very popular. So the twin draws of illegal drinks and a hot band was very attractive. Some speakeasies were world class clubs in their own right, and while most closed down for good once Prohibition was repealed, some establishments still exist today. New York’s 21 Club is an example: Originally opened in 1922 as a speakeasy by cousins Jack Kreindler and Charlie Berns, it was raided twice during Prohibition, but Kreindler and Berns were never caught. After Prohibition ended, they turned the club into a legitimate business and continued to own and run it for another fifty years before selling it to new owners.

The following is an excerpt from TWO PARTS BLOODY MURDER. In it, Trooper Leigh Abbott and Medical Examiner Dr. Edward Rowe investigate a newly discovered Prohibition-era speakeasy, hidden away for almost eighty years. But then they find something mysterious about the back room…

Stepping away from the wall, Leigh turned off her flashlight and slid it into her pocket as she simply tried to take it all in.

A dark wood bar stood at one end of the room, its long smooth surface dulled by dust and grime. A tall square bottle with a yellowed label lay on its side, cork removed and precious contents long since spilled. At the far end of the bar, a sepia poster reading “Alfred E. Smith for President—Honest. Able. Fearless.” hung over an open brass case with several disintegrating cigarettes still tucked inside.

Plaster columns topped by decorative capitals studded the outer walls. Tables were tucked between the columns, and the chairs around them—some tipped over, several broken—told a tale of rough handling and a rapid exit. A lone shoe—black leather with what must have been a scandalously high heel for the time—lay under one of the chairs shoved against the wall.

A blackjack table stood against another wall, scattered playing cards spread over the crumbling green felt surface, and a stack of chips still in the slots. Behind the table, a mural depicting Roman ruins splashed across the wall: crumbling archways, weathered statuary, and toppled Tuscan columns, all painted in cascading shades of blue.

A single forlorn music stand stood on a small raised dais in the back corner, as if waiting for the band to return.

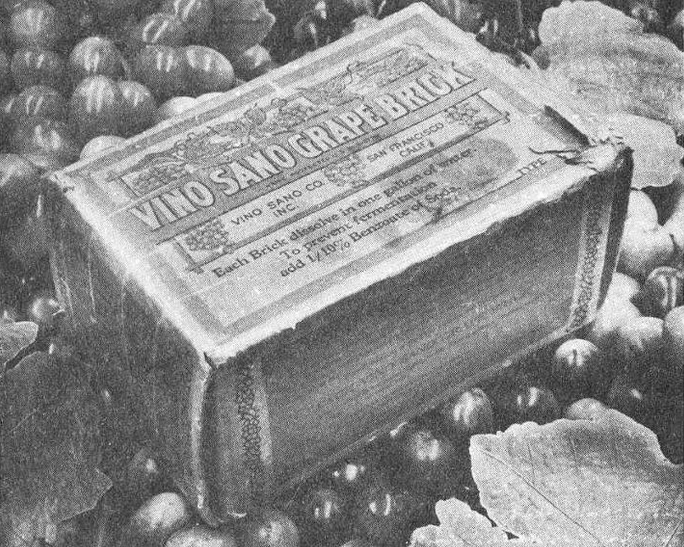

Leigh circled behind the bar. Underneath, dusty shot glasses were stacked in rows, and two beer kegs were tucked under the long stretch of the bar, brass taps tarnished with age. Leigh grasped one of the smooth wood handles and pulled, but not even a single drop leaked out. Large glass jugs littered the floor behind the bar, some tipped over carelessly on their sides. Several wooden crates labeled by out-of-state wineries were stacked haphazardly in the far corner.

Seeing a slip of paper under one of the kegs, she tried to catch it with her fingertips. It took several tries before she drew out a two-dollar bill. Pulling out her flashlight, Leigh aimed it at the bill to study the details. “Get a load of this.”

She passed Rowe the bill over the bar. He aimed his own flashlight at it, examining it carefully. “Two-dollar bill, series nineteen-twenty-nine.” He looked up at Leigh. “That was the first year those bills were printed at their current size. Before that, they were quite a bit bigger.” He flipped the bill over. “Look at that. Monticello on the back, not the Declaration of Independence. Probably not worth much on the open market, but worth an awful lot to a collector.”

“Finders keepers as far as I’m concerned,” she said, and then purposely turned her back on Rowe to examine a poster from the Salt Lake Brewing Company, extolling its Old German lager as “The American Beauty Beer” and promising a restful night’s sleep, a stimulated appetite, and a “nourishing and strengthening tonic for mother and baby.” That last left Leigh staring open-mouthed long enough that when she turned around, Rowe was standing alongside the blackjack table and the two-dollar bill was nowhere in sight.

Coming out from behind the bar, Leigh stood in the middle of the room. As she turned in a slow circle, she felt thrown back in time, a black and white movie playing in her mind as she scanned the room. A tall, broad man in a dark shirt with a white towel thrown over his shoulder stood behind the bar, backlit by rows of gleaming bottles of golden whiskey and ruby wine. Men in London drape suits holding lowball glasses sat at tables across from sparkling women sipping goblets of wine while brandishing long, slender cigarette holders. In the corner a four-piece brass band was blasting out the latest jazz tune. Women with short hair and shorter skirts crowded the dance floor, doing the Charleston and the Black Bottom. The smoky air was full of laughter and song.

“Abbott, I think you should see this.”

Leigh shook her head and the music died away to a mere echo from the past. Her eyes focused once again on the dim, abandoned room. But there was no sign of Rowe and his voice was muffled, although she wasn’t sure if it was from the music in her head or from his location. “Where are you?”

Rowe poked his head out from a swinging door behind the bar. “Over here. There’s a storage room in the back.”

She followed him into a flurry of tipped boxes and spilled bottles. She stopped in the doorway. “Wow. If we had questions before about whether this place was raided . . .”

“It was raided all right, no question. But I wanted to show you this.” He pointed at the wall at the far end of the room.

Leigh picked her way through the crates to stand as close as possible. “What about it?”

“Did you notice that while the walls out there are plaster, the walls in here are just plain brick?”

“Sure. Why gussy up the storeroom when just plain brick will do?”

“Fair enough. But why is this wall different?”

Leigh stood back to look more closely at the room as a whole. The front and side walls of the room were composed of rough bricks in varying shades. But the back wall was uniform in color and texture, and the mortar was shades lighter in tone. “Good question.” She ran her fingers over the bricks on a side wall and then over the back wall. “These bricks feel different. Smoother.”

“I want to try something.” Rowe slipped out of the room, returning moments later with a wooden baseball bat.

Leigh stared at him, dumbstruck. “Where on earth did that come from?”

“Behind the bar. I bet the barkeep kept it around just in case things got out of hand. In the rush to leave, it got left behind.”

“Or after everyone was taken out,” Leigh said. “What exactly did you have in mind?”

“I want to test that wall.” Rowe put the bat down, tip to the floor, and casually leaned on the flat end of the grip. “Why would that wall be different?”

“It wouldn’t be if it went up at the same time.”

“Exactly my point.” He picked up the bat, cradling it in both hands and frowned. “An antique Louisville Slugger. Now this is a crying shame.” He tossed the bat in the air, deftly catching it in both hands, choked up, and swung it at the side wall. The bat hit with a loud clunk and a few flakes of brick fell from the surface to tumble out of sight behind a crate.

He moved to the back wall, tightened his grip, and swung again. The bat connected with the brick with a decidedly higher pitch. Rowe’s raised eyebrows gave Leigh an I told you so look and moved on to the third wall, then the fourth.

They had their answer.

TWO PARTS BLOODY MURDER — coming soon!

Available in hardcover and eBook, you can find TWO PARTS BLOODY MURDER on line at Amazon.com, Amazon.ca, Amazon.co.uk, and Barnes and Noble, and in stores at Chapters/Indigo and at your local independent sellers!

Available in hardcover and eBook, you can find TWO PARTS BLOODY MURDER on line at Amazon.com, Amazon.ca, Amazon.co.uk, and Barnes and Noble, and in stores at Chapters/Indigo and at your local independent sellers!

12.1%

12.1%