On Hiatus This Week...

/I’m away this week with my daughters on a combination family vacation and research trip for my series. I’ll be back on August 2nd with some pictures and stories from my trip. See you then...

I’m away this week with my daughters on a combination family vacation and research trip for my series. I’ll be back on August 2nd with some pictures and stories from my trip. See you then...

As writers, we’re often looking for great resources for learning or strengthening our craft. There’s a lot of information out there in various forms ―books, blog posts, webinars, conferences and more ― but I’d like to shine a spotlight on the Writing Excuses podcast.

I’ve been listening to this podcast for years now (episodes can be found free-of-charge on iTunes or handily archived on the Writing Excuses website). Initially run by fantasy writer Brandon Sanderson, horror writer Dan Wells and web cartoonist Howard Tayler, they have recently been joined by puppeteer and author Mary Robinette Kowal. Their tagline is ‘Fifteen minutes long, because you're in a hurry, and we're not that smart’ ― catchy, but utterly untrue because they really are that smart. These four professional writers bring their own experiences to the table to produce a short, tight lesson in each and every episode. It’s a gold mine for those just starting out. When I first started to listen, they were already well into season three. But what I learned in a few short podcasts convinced me that I needed to download every episode from their past seasons. The information contained in those episodes was invaluable as I was finishing revisions on my manuscript and moving into the query process.

The topics they cover range from the craft of writing to the business of publishing: the basics of queries, brainstorming, world building, submissions, plot twists, voice, killing your darlings, traditional vs. self-publishing, editing, pacing and much, much more. They record and post any sessions they give at conferences, and they frequently invite guests to the show to focus in on his or her specific area of expertise. If you want to learn the craft and business of writing, there’s no better way than learning from those in the trenches. They usually discuss genre fiction and tend to lean more heavily towards sci-fi and fantasy writing, but all writers will come away from this podcast with some tidbit of new and useful knowledge to apply to their own writing.

I highly recommend this podcast to someone who is looking to expand their knowledge about their craft and is looking for an alternate way to learn. Give it a try the next time you’re driving to work or doing the dishes; those fifteen minutes may prove to be the most useful time you spend all day.

Photo credit: Jess Newton

It’s a situation that occurs all too often ― the remains of a victim are found, but all that’s left is an unidentified skeleton. How can police solve this mysterious death if they don’t even know who the victim is? Several key pieces of information are needed to identify a unknown victim ― sex, age, race and time since death ― but without flesh or identifying documents, how can any of this be established?

A forensic anthropologist can determine this information given nothing but the skeleton itself. It may look like smoke and mirrors, but really it’s all about knowing which small details to look for. Add up those small details and a convincing picture appears, and, hopefully, a reliable piece of information can be added to the missing pieces of the puzzle.

So what are the details a forensic anthropologist looks for?

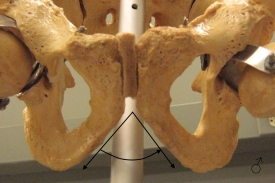

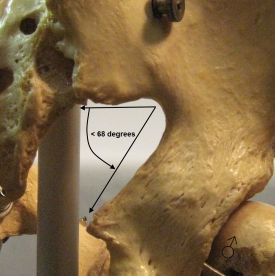

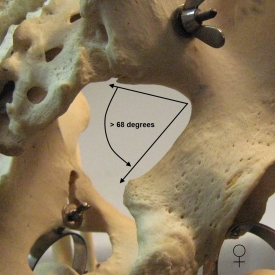

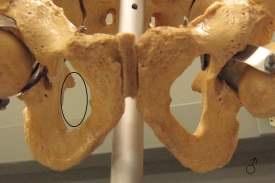

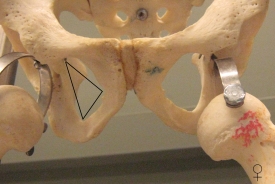

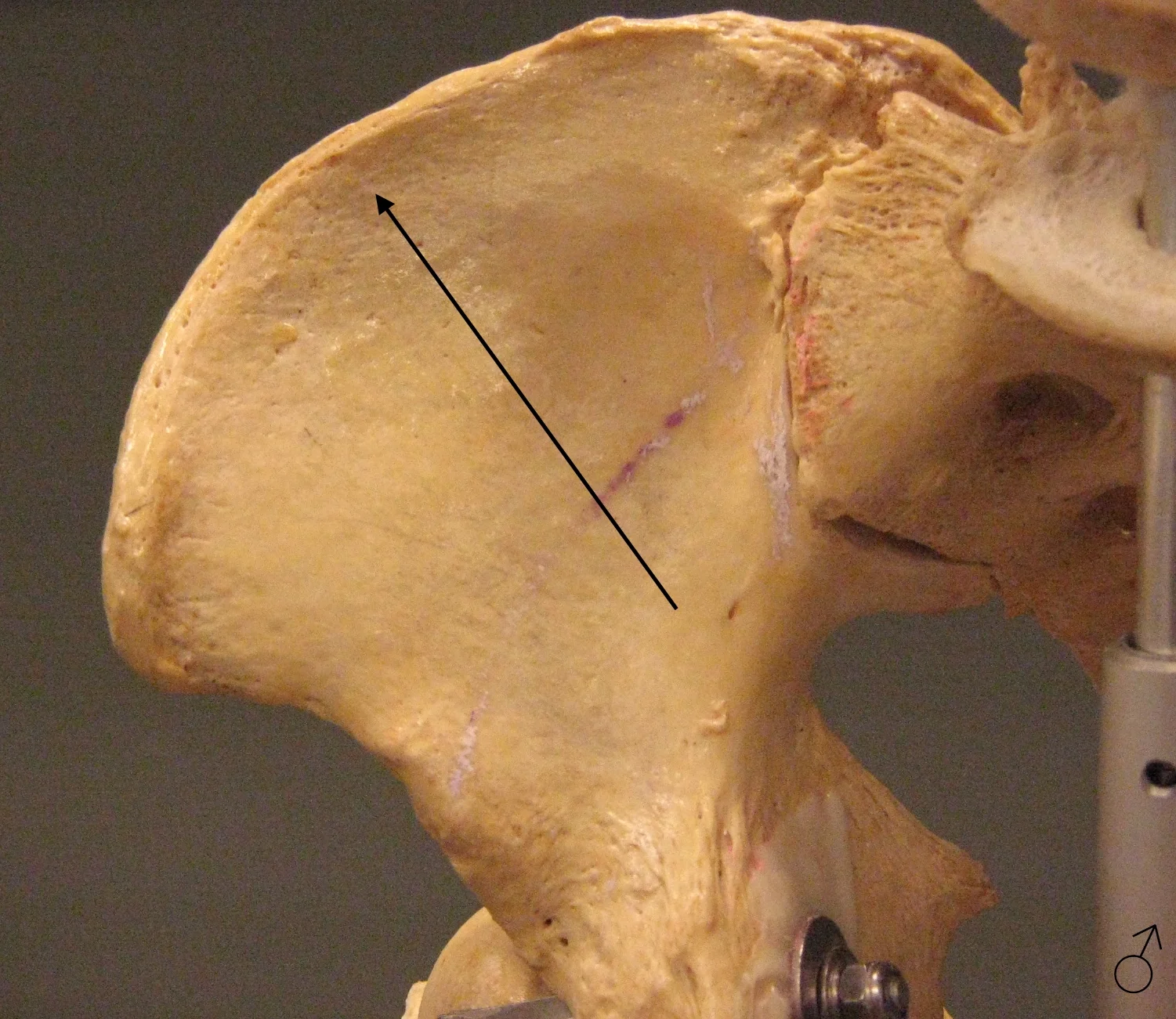

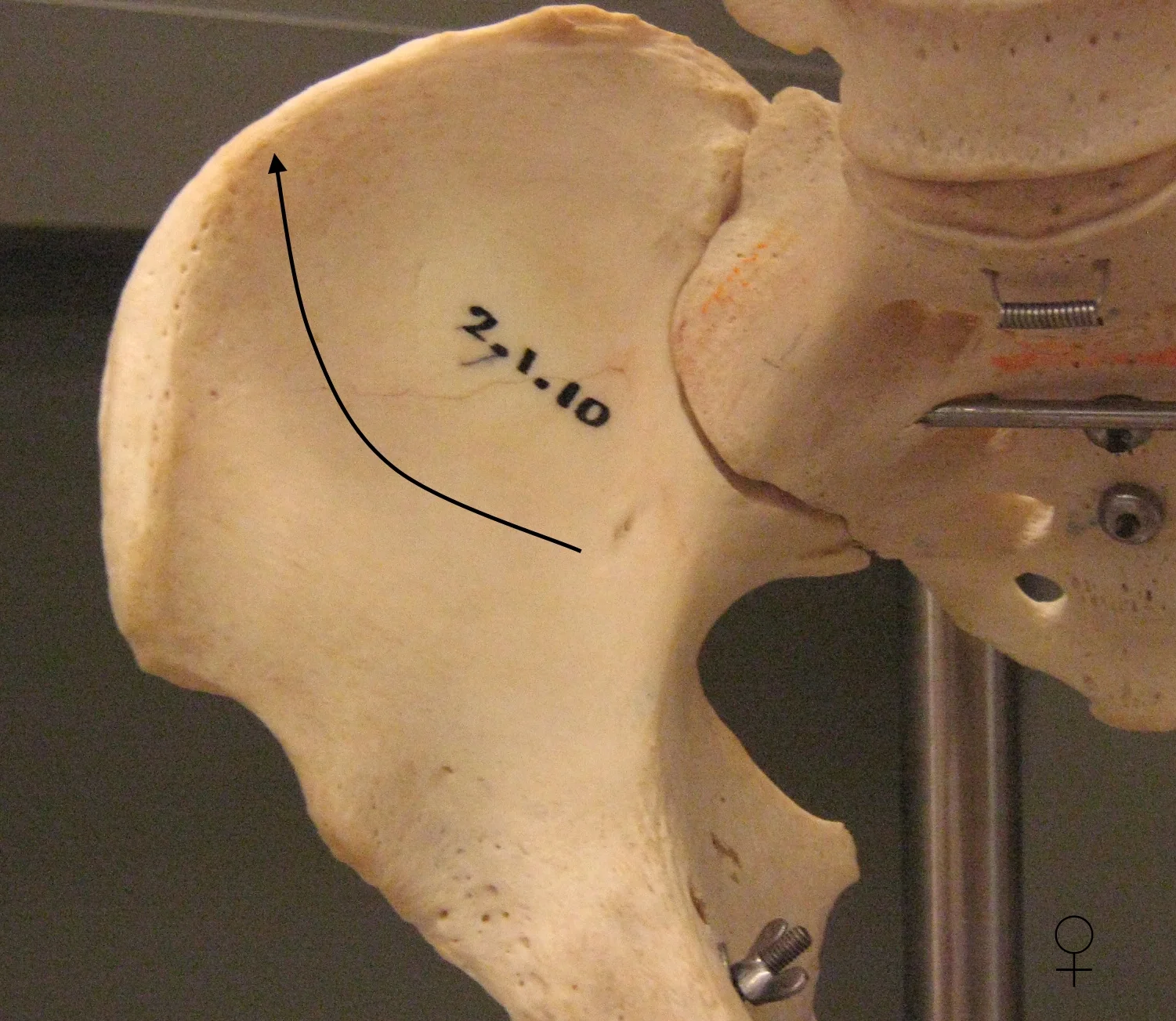

When it comes to sexing an adult victim solely from skeletal markers, the pelvis remains the most reliable feature. Pelvic sexing of children and preteens can be very difficult due to the lack of difference between the sexes before maturity.

There are several specific physical characteristics in the pelvis that are different between the sexes:

Because of variation between people, some of these sex differences might be more or less pronounced, so the use of multiple markers is crucial. Better yet is using multiple skeletal elements (if they are available) to confirm the estimate. In our next Forensics 101 post, we’ll look at how to determine sex of a victim based on the skull.

Thanks to the McMaster University Department of Anatomy for providing skeletal specimens.

There’s a rule in my household ― when I watch TV crime shows with my family, I’m not allowed to comment on the episode. This comes from years of watching shows with me and listening to me gripe about all the things that are wrong with the episode. There’s usually a lot they do wrong.

Sometimes I think it would be more fun to watch TV if I didn’t know as much as I do. But I have a significant knowledge of forensics from years of detailed study, and a growing knowledge of homicide and general police protocols, and there’s no going back now.

Last year, while attending Bloody Words 2010 in Toronto, it was comforting to sit in on one of the forensics talks (given by a member of the Toronto Police Services) and to hear many of my own views reflected back to me. Apparently, flashy TV storytelling doesn’t just irritate scientists; it really irritates law enforcement as well.

But this kind of flashy storytelling isn’t just seen in TV screenplays. It can also be found in crime fiction. And nothing jerks me out of a story faster than inaccurate details.

So what kind of issues really drive the scientist in me crazy?

Science that is conducted at the speed of light ― when DNA or mass spec results only take minutes. At best these protocols take hours; I know, I’ve done them myself. In reality, if a state lab is involved, it can take months or years to get results back.

Test results that are rarely ambiguous and usually point directly as a single suspect. Let me assure you, as much as we’d love it to be black and white, science often isn't.

Every case is solved successfully. I realize that TV screenwriters need to have 22 cases per year and they can’t leave the majority of them unsolved if they want to satisfy their audience. But leaving the odd case unresolved is realistic and would open the door to some great character-based storytelling.

Police officers who blithely cut legal corners or disregard Miranda rights because the plot requires that they do so. In many cases, a little more time spent working out the plot would provide a legal way to achieve the same goals.

Scientists with unrealistic skills. In reality, scientists that are experts in their field are very specialized in their specific niche. In other words, they don’t do DNA and fingerprinting and ballistics with equal proficiency. In reality, different areas of the lab perform specific tests. For very specialized testing, evidence is often sent off-site, perhaps even out of state.

Unrealistic science. Shining a black light on untreated blood will not make it fluoresce, no matter how convenient that might be.

Unrealistic databases. AFIS is a great example of this. The FBI runs a system called IAFIS, but it is in no way as useful as the TV version of AFIS. With only 66 million civilian prints in the system, the chances of finding a match (especially to a partial) is much lower than you would think considering how successful TV detectives are. Realistically, this system takes four to five hours to process a single request, and then police departments will not accept those results as a positive match until a human expert has compared the prints.

Expert witness who conveniently have connections/previous ties to the department, thereby undermining their credibility at a crucial moment in a trial. In reality, witnesses are screened with excruciating care, ensuring that this rarely happens.

My point in this list is that a lot of this could have been avoided if a little more time was spent plotting. Yes, in a forty-two-minute TV show, they can’t write in a two month wait for DNA results, but sometimes they swing so far the other way that it’s laughable. Use realism if you can and let your characters react to it. The trick to writing realism is to find a way to hook your reader and them keep them drawn into the story through characterization, no matter how long the lab results take.

I can’t be the only one with a list of pet peeves when it comes to storytelling. What drives you crazy?

Photo by striatic

12.1%

12.1%Blog Tags

Blog Archive