Playing Hooky Is Good For The Soul

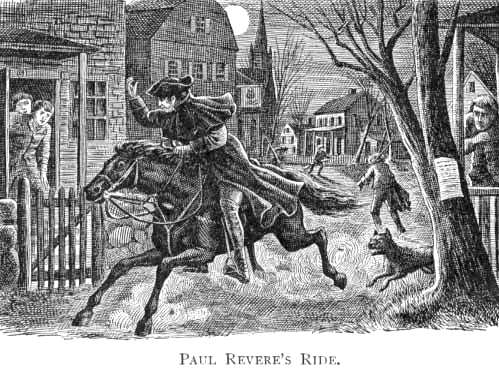

/Ann and I were supposed to be working most of this weekend on a new project. After a week of research, this was when we’d agreed to start putting our respective heads together to get the planning off the ground. But when it’s Thanksgiving weekend in Canada, it’s 26oC/79oF without a single cloud in the sky, and you know that within six weeks the snow will be flying... well, let’s just say it’s not hard to talk yourself into heading outside instead of sitting inside staring at your monitor.

On Sunday, after a really productive morning of joint planning, I played hooky and went out with the family for a hike in a nearby conservation area. So, instead of my regular blog post on writing or forensics, today I bring you instead the beauty that is fall in Southern Ontario (because apparently I’m playing hooky on the blog too). Special thanks to my oldest daughter for her photography skills as well as her mad Photoshopping skills because all nature looks nicer with no people in it!

It was a beautiful, peaceful and fun few hours away from work. And I came back recharged and ready to hit the keyboard again. I don’t do it very often, but occasionally playing hooky is good because sometimes we all just need a break and a breath of fresh air.

Sunlight breaking through the trees

Sunlight breaking through the trees

Tewes Falls

Tewes Falls

The view from Dundas Peak

The view from Dundas Peak

So who else played hooky this weekend? It was a beautiful weekend in the northeastern States and Ontario. I know I wasn't the only one. Come on, 'fess up!

Photo credit: Jess Newton

87.5%

87.5%