Biosecurity Incidents In Top U.S. Labs—Biosafety

/

This post may be a little off the beaten path for some of our blog readers, but it’s a story I’ve been watching over the past year or more. And when a new twist on the story hit the news in the last week, I thought it might be a good blog topic, even though it doesn’t have anything to do with writing or forensics. In this case, I’m looking at something near and dear to my day job—infectious diseases research.

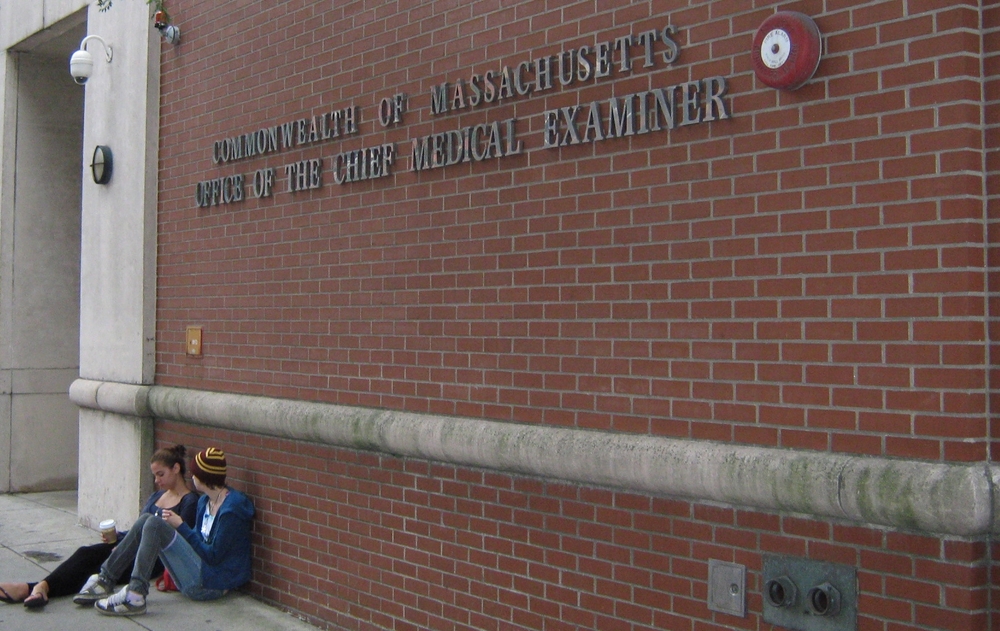

In July, 2014, several alarming announcements came out of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) involving potential and proven accidental exposures of lab personnel to extremely infectious pathogens. Then, that same month, the NIH announced the discovery of an even more dangerous pathogen found forgotten in FDA freezers. Just last month, the Pentagon admitted that one of its Army labs sent live pathogen out to as many as 69 different labs in a number of different countries. And now, this past week, it was revealed that same lab was secretly sanctioned for those actions eight years ago, but this information was hidden from Congress, which is responsible for oversight of the lab.

It’s enough to give a person nightmares about biological disasters.

Before we get into what went wrong with labs the world considers the gold standard in biosafety, let me give you a little bit about my background. I’ve worked at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario for nearly 25 years. I sat on the university’s Presidential Biosafety Committee for 5 years, making decisions on how to implement government standards for the safe use of pathogens, and how to rectify procedures that resulted in accident. I’ve worked nearly 25 years with biosafety level II pathogens (herpes simplex viruses I and II, vaccinia virus, Adenovirus, influenza, dengue virus and many others), and for over 15 years with biosafety level III pathogens (HIV and herpesvirus saimiri). Biosecurity has been my life for my entire adult working career.

What exactly does ‘biosafety level’ mean? The biosafety level of a pathogen is based on a number of factors: infectious dose (i.e. how much is required to contract the disease), mode of transmission (i.e. blood borne vs. air borne), host range (i.e. human vs. animal or both), the availability of effective treatment (i.e. pharmaceuticals), and the availability of preventative treatment (i.e. vaccines)

There are four internationally recognized biosafety levels for pathogens:

- Biosafety level I—an organism unable or unlikely to cause disease in healthy individuals. May cause disease in immunocompromised individuals.

- Biosafety level II—infectious organisms that cause disease, but are unlikely to make an individual seriously ill under normal circumstances. Effective treatment and preventive measures are available, and the risk of spread is limited. Example: herpes viruses, including those that cause mononucleosis, chicken pox and roseola.

- Biosafety level III—infectious organisms that cause serious disease, but do not spread by casual contact. Organisms that cause diseases treatable by antimicrobial or antiparasitic agents. Example: HIV, anthrax.

- Biosafety level IV pathogens—infectious organisms that cause very serious disease, often untreatable and leading to death, and are spread by casual contact. Example: Ebola virus.

Different containment levels are required to study pathogens at different levels.

- Biosafety level I pathogens, like many strains of non-infectious E. coli, can be used on the open bench in the main lab.

- Biosafety level II pathogens must be used within a separate level II room in a biological safety cabinet. Air is drawn into the cabinet away from the user and only exhausts into the room after HEPA filtration, thereby keeping any infectious particles trapped inside the cabinet. The user only interacts with the pathogen after donning a lab coat and gloves and by remote access i.e. using a pipettor to actually contact/transfer the pathogen.

- Biosafety level III pathogens are used in an isolated, approved access-only laboratory with negative pressure similar to a biosafety cabinet—air is drawn in from outside the laboratory and only exhausts from a laboratory through giant HEPA filters in the ceiling. Workers inside the facility must wear rear-closing gowns and double gloves at all times. In the case of airborne pathogens, workers must also wear respirator hoods with a powered air purifier worn on the belt. A safety shower must be located in the laboratory in case of spills and pathogen appropriate disinfectants must be available at all times. In case of incident, detailed reporting and follow-up is mandatory.

- Level IV pathogens can only be used in biosafety level III style labs situated in an isolated building. Work will involve all the requirements of biosafety level III work, but over and above that, the use of a positive pressure personnel suit (which pushes air out of the suit and away from the user) is mandatory at all times. Multiple showers (both in-suit and out), a vacuum room, and a UV room are required for clean exit from the facility.

Specialized training for each specific biosafety level is required by all personnel, often with annual updates and review. As you might imagine, the complexity of the training increases in orders of magnitude as the biosafety level increases.

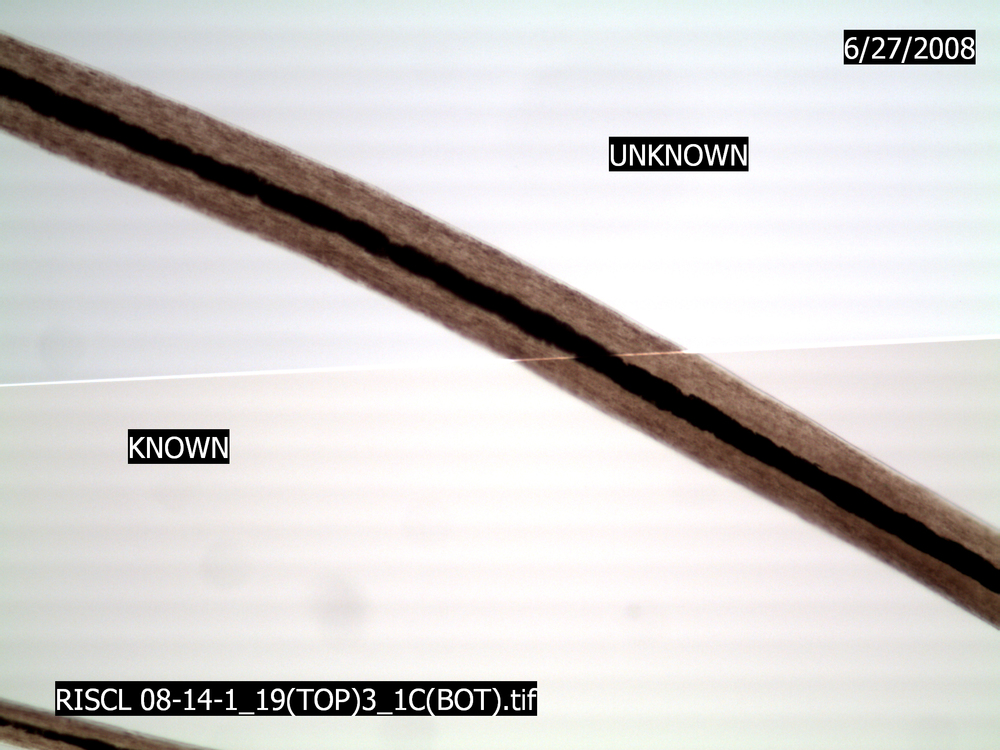

Another aspect that is crucial to biosafety work, especially at upper levels, is tracking—where pathogen is stored, how it is treated, when small volumes are removed, how they are used, and how they are destroyed. There are strict guidelines concerning any transfers outside the laboratory as well—how it can be removed and who is allowed to receive it based on their facilities and training.

So now that you understand some of how this work is done, next week we’re doing to look at what went wrong (when it absolutely shouldn’t have) and what’s being done to safeguard workers and the public. See you then!

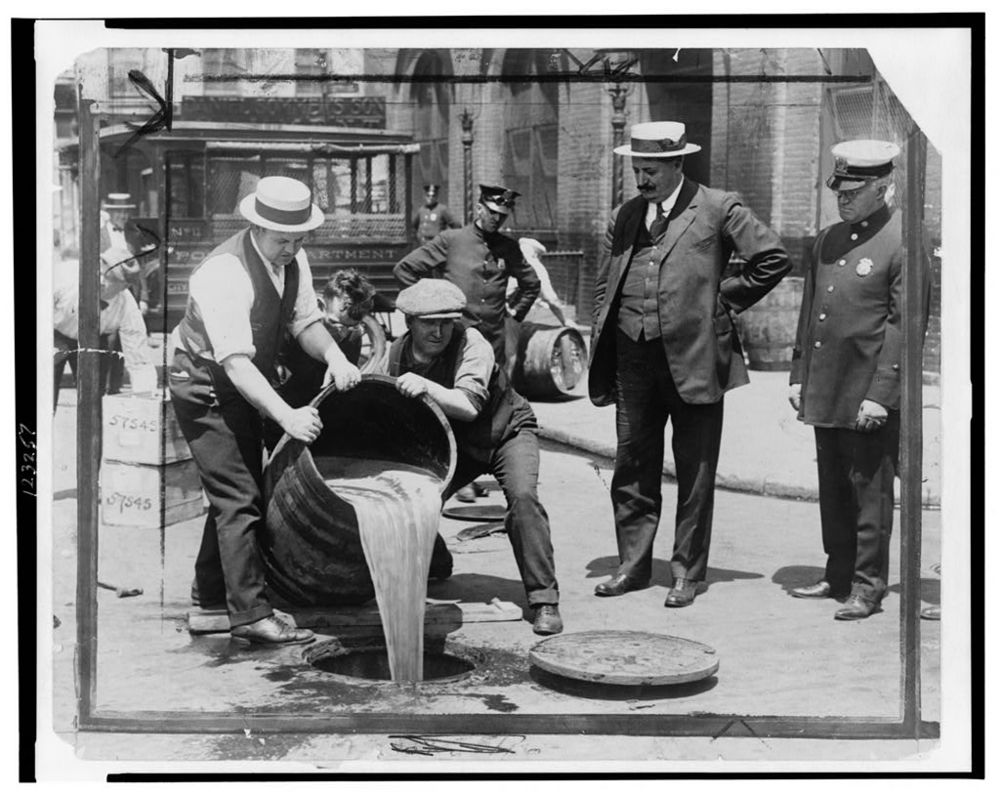

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

87.5%

87.5%