Recognizing When Your Plot Is Drifting Off Course

/ About nine months ago, I wrote a blog post about the planning method we used to write Dead, Without a Stone to Tell It. In that post, I discussed that instead of using our usual detailed-to-within-an-inch-of-its-life outline, Ann and I attempted something different — more of a freeform approach where we planned the beginning in detail and left the specifics loose to allow for a little more creativity, while still having a rough idea of where we wanted to go. When it came to writing A Flame in the Wind of Death, the second book in our series, we used a similar plan. The beginning of the book was well planned out and we knew the details of the murders and who was committing them, but we left ourselves some room to explore as we wrote.

About nine months ago, I wrote a blog post about the planning method we used to write Dead, Without a Stone to Tell It. In that post, I discussed that instead of using our usual detailed-to-within-an-inch-of-its-life outline, Ann and I attempted something different — more of a freeform approach where we planned the beginning in detail and left the specifics loose to allow for a little more creativity, while still having a rough idea of where we wanted to go. When it came to writing A Flame in the Wind of Death, the second book in our series, we used a similar plan. The beginning of the book was well planned out and we knew the details of the murders and who was committing them, but we left ourselves some room to explore as we wrote.

Every book is different, and where that freeform style worked well for Dead, I knew last week that I was having problems with Flame. The first 60% of the book was written and I know exactly how the last 25% was going to fall. The issue was the section in between. Not knowing exactly how to link those two parts of the story together was slowing me down. The plot line I was seeing for that part of the case was simply too straightforward for a mystery. I knew the waters needed muddying, but I wasn’t sure how to do it. It wasn’t that I had writer’s block, but I knew uncertainty was getting in the way of the words flowing.

So what do you do when your plot seems to be drifting away from you?

- Stop spinning your wheels: If what you’re doing now isn’t working, stop and step away from your manuscript. The longer you bang your head against it and the more frustrated you become, the less likely you’ll be able to figure out the real problem.

- Reread from the beginning: Go back and a review what you’ve written. It’s amazing the details you can forget in even a few short weeks. Makes notes as you go to strengthen your manuscript and be open to any plot points that leap out at you. The answer to the issues that blocked you may be contained in sections you’ve already written.

- Brainstorm with a crit partner: If you’ve got a crit partner who is willing to help out, bounce your plot and some potential ideas off them, and then be open to consider their suggestions.

- Go back to the outline (if you have one), re-outline if necessary: If not having a roadmap paralyzes you, go back and fill in the blanks in your outline. Sometimes it’s easier to deal in bullet points than scenes and chapters. When you can see where the plot is going directly, you can often see the holes in it.

- Up the stakes: Sometimes you’re not feeling the love for your manuscript because there’s simply not enough at stake. If you’re bored with your vanilla plotline, just imagine how a reader will feel. Remember that tension and conflict drive plot, so go back and crank up those aspects of your storyline.

- Re-evaluate character priorities: Do your characters’ motives seem out of sync with their own personalities? The disconnect you may be feeling with your storyline may simply be your subconscious recognizing that you’re not being true to your characters. Make sure that their actions and motives seem genuine and won’t yank your reader out of your prose simply because of out-of-character behaviour.

- If all else fails, give yourself a break from the project: Sometimes the best thing you can do for your own work is give yourself some perspective on it. Often the best way to do that is to put it away for a few weeks, if not longer. Sometimes we’re simply too close to our own writing to see its flaws and distance is wonderful for allowing you to view your own work with a critical eye.

So how did I get past this block in my work-in-progress? The first thing I did was stop writing new material and then I spent last week-end rereading the 60,000 words we already had down. A few things leapt out at me right away simply from that exercise. But then Ann and I went back to basics and really nailed out the last third of the book. We spent some time brainstorming and building off each other’s ideas. Together, we worked out the kinks and outlined the final section of the book. Now it’s full steam ahead and we should have the first draft completed within a few weeks.

For the writers in the group, how do you manage when your plot starts to drift or you lose the thread? I’d love to hear your suggestions in the comments.

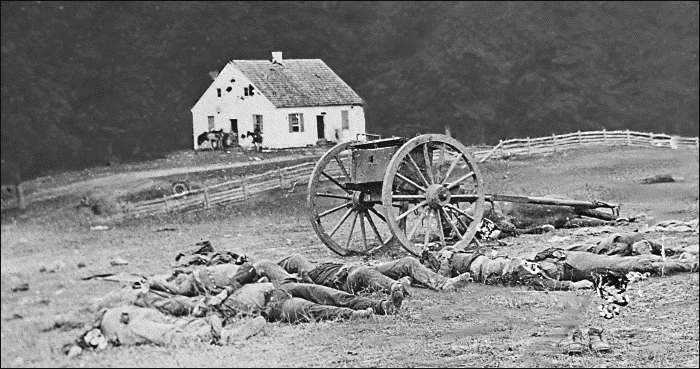

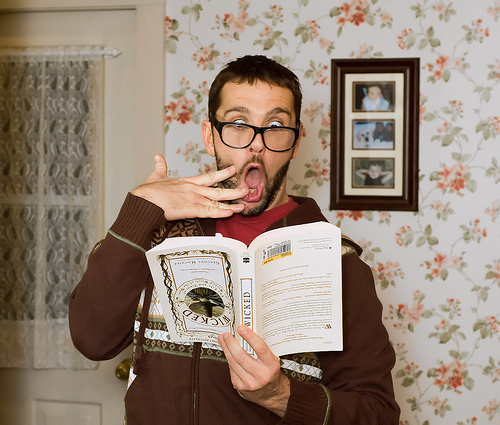

Photo credit: bigcityal

5.2%

5.2%